I’m sure you will read this elsewhere, but here I go anyways. Wizards of the Coast has announced that the core AD&D books will be reprinted in early 2012. New covers, original interior art, limited edition (unfortunately). The price looks to be in line with other standard hardcovers, which is nice. They are supporting the Gygax Memorial Fund with some of the proceeds.

Monthly Archives: January 2012

Ancient Power Armor

Suits of ancient power armor are remnants from an age of lost technological marvels. Most suits will be found in varying levels of disrepair, and are sometimes mistaken for statues.

Power armor operators have AC as plate. The suit of armor has a pool of hit points which is depleted prior to the user taking any damage. Each suit of ancient power armor has a level, which corresponds to the number of hit dice rolled for max armor HP. For example, a 6th level suit of armor will have 6d8 HP. To randomly determine armor level, roll 2d4.

Movement while wearing power armor is 90′ (3/4 unencumbered human movement) but is not decreased further by any but the most extreme encumbrance. Depending on the suit in question, using conventional weapons may be awkward (resulting in an attack roll penalty).

There is a 50% chance that power armor will have offensive systems, which by default are a pair of energy canons (one mounted on each arm). Each blast consumes a charge from a super science battery, and does 1d8 damage per blast. Both arm canons may be fired in a single round.

Operating the power armor requires a successful “use super science” check. This is 1 in 6 for most classes, 2 in 6 for dwarves/engineers (*); the chance is also raised by 1 for high intelligence (13 or greater). No more than one check per character is allowed per suit. One check is required for mobility and defensive systems, another check is required for offensive systems, if they exist. A week of work, plus another successful super science check, will repair 1d8 HP worth of damage. Referee ruling may require special materials or GP expenditure as well.

When the power armor HP is reduced to 0, it ceases to function immediately, damaged beyond repair. Any extra HP damage spills over onto the user. Extraction from the suit requires 1d4 rounds and a successful strength check, or a full turn of careful manipulation.

In no circumstances can a wearer of power armor ever cast spells or use magic items.

Many varieties of ancient power armor exist. For example, some are designed to function underwater and supply oxygen. Others have variant offensive systems, such as flame throwers. Some suits of power armor also grant immunity to certain forms of attack, such as fire or electricity.

(*) I haven’t posted in detail about it yet, but the engineer is a human reskin of the dwarf B/X class.

A 4E player & OD&D

Wherein I comment on the discovery of OD&D by a 4E player and DDI contributor.

First, here are the relevant blog posts, in chronological order:

- From OD&D to Playtesting New Editions… and Back Again

- OD&D and the Challenge of Pleasing Everyone, Part 1

- OD&D and the Challenge of Pleasing Everyone, Part 2

It’s always interesting to see the reactions to OD&D from players of later editions.

Here are some quotes interspersed with my comments.

With five PCs (one charmed) and 10 Nixies, the result was a TPK. And yet, we were all laughing and having a blast.

Remember that thing about DM control? The PCs came to underwater, in an air pocket in the Nixies’ lair. After some fun interaction they allowed the PCs not to serve them for one year, and instead they had to go to the Temple of the Frog and end the threat.

Now, that might sound like he was being a pushover DM (there was, after all, a TPK), but I actually find myself enjoying the development. As a referee myself, I don’t like undoing PC death, but if I had decided beforehand that the nixies were just trying to subdue (even if before meant as I was rolling up the encounter at the table), I would have felt better about it. What a great lead-in to Temple of the Frog though: servants of nixies for a year.

Ian of the Going Last podcast, largely held to be a cheese monkey, cast Charm on my hireling. He then told my hireling to kill himself. Checking the rules, they had not yet added the errata to stop this. Ok, I figured I would let this one happen. Now Ian asks about XP. Sure. They get 100 XP, plus 100XP more for his equipment (since in these editions you get XP for gold). Well played.

I think this is pretty clearly against the spirit of the game, which gives XP for treasure recovered and danger faced.

My feeling is that 4E creates these big set-piece combats that are often inside rooms and consume a big part of a play session. Because of that, we lose all the other bits (the exploration, the movement, the empty rooms we still search, etc. The dungeon ceases to feel extensive, mysterious, holistic, ecological. Those other bits end up being important to the experience.

I couldn’t have said it better.

All damage was a d6, which led the players to have fun with unarmed attacks, throwing a crossbow bolt by hand, and other silly things that still do d6 damage on a hit. In general, combat was more descriptive.

An important assumption of OD&D, in my mind, is that unless otherwise stated things work relatively realistically. This is the wargaming context at work. In other words: I don’t think the rules suggest that a thrown crossbow bolt should be considered a weapon. There’s nothing wrong, of course, with running a cartoon game where thrown pebbles also do 1d6 damage, if that’s how you roll, but nothing in the rules compels such an interpretation. Taking a crossbow bolt and plunging it into an enemy’s eye? Cue Heath Ledger Joker voice: “Now we’re talking.”

(Why is it that 4E’s powers, so descriptive in nature, don’t result in players being more descriptive? I would love to see D&D Next find a nice balance between robust options and imagination.)

I have definitely noticed this in my 4E Nalfeshnee game. I think that is in part because many of the powers are just not very describable. Many seem out of place; a particularly egregious example being the bard power war song strike, which just becomes ridiculous ofter one or two uses (it is an at-will power). Also: perhaps player description has an inverse relationship with power description. In fact, I would argue that we can generalize this. Description and flavor are a fixed quantity. If the setting and rules supply more, the players (including the referee) will supply less.

no level is suitable for the rooms with 250 guards

Here I strongly disagree. This area is suitable for any level as an obstacle. Remember those scenes in the original Star Wars on the Death Star with the battalions of storm troopers? Han et al sneaked around. Same thing. The idea that everything should be fought head-on and killed is one of the more pernicious RPG trends (actually, I blame video games more than 3E and 4E).

Fight On! and Space Beagles

I received a couple of nice items today. The first is a holdover from a purchase last year.

The Fight On! Issues #1-4 hardcover. I have all the issues of Fight On! in PDF, but this is my first hard copy. Among (many) other great articles, issues 2 and 3 contain Victor Raymond’s excellent Wilderness Architect series (the pair of articles together is one of my favorite old school supplements). Unfortunately, there is no comprehensive table of contents or index (the pages aren’t even renumbered to match the form factor). I’m more or less used to that with books like this by now, but it’s still a shame. This is one thing you can say in favor of traditional publishers: there is no way they would ever release a book without standard apparati. I love the text-free Elric cover though.

It has one serious-looking spine. It is actually the thickest book on my gaming shelf now.

And the next one was a birthday present, The Voyage of the Space Beagle. This novel contains the inspiration for the displacer beast. I was going to read some H. P. Lovecraft after finishing Jack of Shadows (Zelazny), but this one might come up first.

Night Shade CAS Ebooks

Some helpful guy named Scott commented on this Grognardia post that the Night Shade Clark Ashton Smith collections (five large volumes, normally hard to find and expensive) are available from Baen Ebooks for $6 each (or $25 for all 5). These editions are DRM-free and multi-format.

Mnemonic Module Text

Justin Alexander (of The Alexandrian) left a comment about boxed text on a Grognardia post that has stayed with me. (I would link to the comment itself, but recent changes to the Blogger comment system seem to prevent such direct linking.) Justin wrote:

(a) clear separation and identification of all the information the PCs should have upon entering a space makes running a module infinitely easier for the GM; and (b) boxed text is an immediately useful way of making that separation while also providing (when properly executed) a useful tool in its own right.

I agree with this, but though boxed text is intended to be information immediately perceived by PCs, it is often cumbersome to read (with literary pretensions), can be quite long, and often does not include items that the referee should be immediately aware of (say, a pit trap). So while it can help (sometimes), it is not a complete or perfect solution.

As an example, consider this area description from the module I am preparing right now, The Pod-Caverns of the Sinister Shroom:

11. SHAMBLING MOUND LAIR: Ropy pillars of fungus grow from ceiling to floor here, ranging from one to four feet in diameter. A young shambling mound grown by the Shroom makes its lair in the back of the chamber, hidden from sight by the many fungus pillars. In addition to guarding the passage, the shambling mound guards a treasure casket, trapped with a poison dart trap (3 darts, 1d3 damage, poison +3 saving throw, attacks as 2HD monster). The casket contains 1200 gp, 10 pps, 1 potion of healing, and a fungus staff. The staff is made of a spongy fungus material that can be looped or folded (it is coiled in the casket). Whenever combat threatens (e.g., a surprise roll is called for) the staff snaps straight for battle and becomes a +1 quarterstaff in all respects. This ability acts as a warning, granting anyone with the staff in hand to be surprised only on a roll if 1. If it is stored in a backpack or other container, it may very well damage the container when it straightens.

That is quite a wall of text to reread in the midst of play. Note that more than half of the paragraph is treasure description. I had already read the module once through, and I remembered that there was a room with a shambling mound, and I also remembered the fungus staff, but I didn’t remember that they were in the same room, that the chest was trapped, or the important entry description (thick ropes of fungus). This was the text I wrote in the margin:

- thick pillars of fungus floor to ceiling

- hidden shambling mound

- guards trapped treasure chest

Look at how much easier that is to assimilate quickly. It is enough to remind me of all the important aspects of this area. The bullet list is not a substitute for the detailed prose description (which the referee still needs to read beforehand to get a sense of the overall module). Even a concise paragraph of prose text cannot really be read during the play without breaking the flow of the game. If I had not written those notes, I probably would have to reread the entire paragraph to make sure that I was not forgetting anything important.

I don’t mean to pick on Matt’s module, I actually highly recommend it. It’s well written and very creative. Pod-Caverns just happens to be the module I am using right now. This is only a suggestion for module writers intended to help make modules easier to use.

See also: Zak’s posts on annotating maps (and here).

B40 Normal Human

| Revisitation: a series of posts that each feature a quote from a classic source along with a short discussion. Quotes that make me question some previous assumption I had about the game or that seem to lead to otherwise unexpected consequences will be preferred. |

This entry comes from the Normal Human monster entry in Moldvay Basic (page B40):

A normal human is a human who does not seek dangerous adventure. A normal human does not have a class. … As soon as a human gets experience points through an adventure, that person must choose a character class.

So this is how humans in Moldvay D&D become adventurers: not by training, not by having exceptional ability scores, but rather by sheer audacity.

Retainers (at least the kind recruited in a tavern) should probably have the statistics of normal humans. Once they survive their first excursion into the underworld or wilderness, perhaps the player of their employer should be allowed to select the retainer’s class? That would help give the player a stake in the fate of the retainer, and maybe also be a good time to introduce the traditional idea of the retainer as a PC-in-waiting. I’ve liked that idea ever since I read about it, but I have never seen it used in play.

Finding a retainer with a class (like some of the NPCs in Bone Hill) could be a special occurrence, almost form of treasure or reward, rather than a disposable grunt. Especially if that means that dying means that you go back to level N (where N is the level of your highest retainer) rather than level 1. That, however, is probably anathema to many new school players, who suffer from “my precious character” syndrome just as much as many referees suffer from “my precious encounter” syndrome. Many people are only happy with wish-fulfillment characters, which also undergirds much of the drive for being able to control every aspect of character creation.

When discussing normal humans, it is also perhaps worthwhile to note that many monsters in the bestiary are in fact thinly disguised versions of other monsters with minor cosmetic changes and trivial rules differences. There are four alternate type of troll, for example, in the Fiend Folio (giant troll, giant two-headed troll, ice troll, and spirit troll, in case you were curious). I would argue that most of the humanoid races as presented in D&D are pretty much just this. Much like the aliens of Star Trek, they are just humans in makeup.

James Raggi said it better than I could. In the LotFP Grindhouse Edition Referee Book, he wrote (page 51):

Humanoids are basically man-like creatures who have a gimmick and are present merely to give PCs intelligent, organized opponents which can be slaughtered wholesale with little reflection, remorse, or consequence.

…

Whenever you think to introduce a humanoid, just ask yourself, “Why would these not work as humans?” Much of the time it is of the desire to not portray humans of a barbaric bent as savages.

This also allows the referee to keep the truly monstrous humanoids waiting in the wings for portrayals such as Beedo’s Orcs of Gothic Greyhawk or my own Goblins as Corruption. And to make more use of the monster entry on page B40: the normal human.

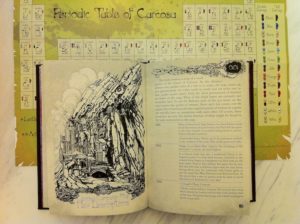

Carcosa in detail

In Carcosa, almost all of the identifiable tropes of D&D are gone, yet the essence remains. There are no dragons, demi-humans, magic-users, or magic items. There is little overlap in the bestiaries other than the oozes, slimes, molds, and jellies (which are cleverly recolored to fit the setting but otherwise pretty much the same).

In Carcosa, almost all of the identifiable tropes of D&D are gone, yet the essence remains. There are no dragons, demi-humans, magic-users, or magic items. There is little overlap in the bestiaries other than the oozes, slimes, molds, and jellies (which are cleverly recolored to fit the setting but otherwise pretty much the same).

The LotFP version of this book has a somewhat odd status. Originally, Carcosa was published as a supplement to the 1974 D&D rules. Though that was seen as presumptuous by some, it made the intended use of the book obvious, at least to someone who was familiar with OD&D and its supplements. Carcosa the saddle-stapled digest book was easily identifiable as the same sort of book as, for example, Supplement II: Blackmoor. This new release of Carcosa is not, in and of itself, identifiable in the same way, though it is still the same sort of book at its heart. This is not a problem for me, but may be for someone less familiar with the OSR community and OD&D in general.

I have organized my thoughts around the entries in the table of contents, which I arranged into several groups of related items and reordered. These groups represent the five different types of content in the book.

Setting

- Sorcerous Rituals

- Monster Descriptions

- Carcosa Campaign Map

These sections are the most tightly bound to Carcosa the setting. The most impressive thing to me is how integrated all these different parts are. Most games separate these parts (think about the PHB, Monster Manual, and campaign setting split of most D&D products). For example, with every monster is a listing of relevant rituals. And many rituals require components which can only be gathered in specific locations (or must be performed in particular locations). I suppose you could steal a hex here, a ritual there, and a few monsters, but if you just pick and choose bits from these sections, you will not be taking advantage of these linkages. This is a template for how to put together a really engaging hexcrawl campaign. Make all the different categories of rules and setting interrelated. The way the pieces fit together, the whole is definitely greater than the parts.

These sections are the most tightly bound to Carcosa the setting. The most impressive thing to me is how integrated all these different parts are. Most games separate these parts (think about the PHB, Monster Manual, and campaign setting split of most D&D products). For example, with every monster is a listing of relevant rituals. And many rituals require components which can only be gathered in specific locations (or must be performed in particular locations). I suppose you could steal a hex here, a ritual there, and a few monsters, but if you just pick and choose bits from these sections, you will not be taking advantage of these linkages. This is a template for how to put together a really engaging hexcrawl campaign. Make all the different categories of rules and setting interrelated. The way the pieces fit together, the whole is definitely greater than the parts.

I would love to see a reworking of the classic D&D magic system along similar lines. Take all the original spells, flavor them up, and then scatter the components required over the hex map. Up the power a bit so that they are more impressive, and also include elements like making spell X only functional at certain times or in certain places. I would be all over that.

- Space Alien Technology

- Technological Artifacts of the Great Race

- Technological Artifacts of the Primordial Ones

- Desert Lotus

Now we come to the toys. That is, things that PCs might play with. The Space Alien Technology functions, I imagine, much like the magic items function in other games (though obviously with a different flavor). There is a random generators in the back for Space Alien Armament also. The “technological artifacts” are likely to be rarer (like artifacts in D&D). You will notice that three of those four categories are the technology of higher-order beings, which highlights one of the main themes of Carcosa (and, in turn, of H. P. Lovecraft, one of Carcosa’s spiritual progenitors): the universe is a vast and unknown place which was not built for the comfort of humans.

Other than humans (the only option for PCs), there are three other major types of being. Space Aliens are about what you would expect from the name. The Great Race is something like Robert E. Howard’s Serpent Men. And Primordial Ones (also called the Old Ones) are incomprehensible, mostly disgusting, Cthuloid entities (many named creatures taken directly from the pages of H. P. Lovecraft). This forms a hierarchy of beings, with humans on the bottom rung, followed by Space Aliens and the Great Race (I’m unsure which of those should be considered more sophisticated or powerful), with the Old Ones at the top of the food chain. Humans don’t really have anything to their name, other than sorcery (which is really just borrowed from the Great Race).

All of these are well-crafted and evocative, and could easily be dropped into any game, or inspire your own artifacts.

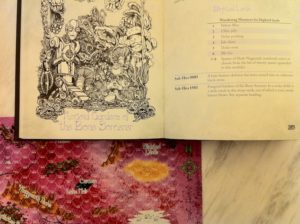

Fungoid Gardens of the Bone Sorcerer

This is an intro module. It also functions as a nice template for how to detail a village without going overboard. Paired with a nice, quick method of randomly generating a village layout (think something like Vornheim), and some practice using such a system on the fly (I’m still getting there), I think this is all you need.

This is an intro module. It also functions as a nice template for how to detail a village without going overboard. Paired with a nice, quick method of randomly generating a village layout (think something like Vornheim), and some practice using such a system on the fly (I’m still getting there), I think this is all you need.

The module is a single 10 mile hex blown up into sub-hexes of 704 yards and includes a number of mini-encounters, adventure hooks, and one small dungeon. I wonder how many such hexes Geoffrey has detailed for his own campaign?

Random generators

- Spawn of Shub-Niggurath

- Space Alien Armament

- Random Robot Generator

- Mutations

This is the most setting-agnostic part of the book, and all of these random generators are easily repurposed, even for games with less gonzo flair. Mutations could be used to add flavor to NPCs, or as the result of a botched spell. The random robot generator is also a random golem (or automaton) generator in clever disguise. The Spawn generator cranks out minor (though still dangerous) Cthuloid entities.

These parts of the book are very strong, and should be useful to every old school ref. One can’t have too many random monster generators (at least, I am far from my saturation point).

New rules

- Characters

- Dice Conventions

At first I felt like the sorcerer class was superfluous. My concern was not originally about balance (the sorcerer might be fighter+, but that comes at the cost of slower advancement). Here is Geoffrey’s explanation for why the Sorcerer is a separate class:

I imagine Sorcerers as men who had to spend 10+ years learning the intricacies of the esoteric language of the lost Snake-Men, and twisting their minds in such a way as to be able to comprehend and effectively perform sorcerous rituals. (Consequently, I can’t imagine any Sorcerers under the age of 30.) Being able to do this is a lifetime commitment. There are no dilettante Sorcerers. Nobody could ever say, “I’m not a Sorcerer, but I’m going to spend the weekend learning how to conjure and bind the Inexpressible Presence of Night.”

And that makes sense to me. It would have been nice if he had said as much in the book. I would probably differentiate the sorcerer a little more, just to emphasize that very difference (a different hit die would work, but for the dice conventions). Also, if sorcerers have spent 10+ years mastering the intricacies of sorcery on such a primitive world, why do they get the same base attack bonus as fighters? I would probably cut that in half, or go the LotFP route and have sorcerers never get better at fighting. The game would also function if you imported any classic set of classes, and allowed anyone to perform rituals given the proper components and configuration, though the feel would change slightly.

I think the dice conventions are important, though they are likely to seem very foreign to many readers. They show the level to which D&D can be hacked and still maintain integrity. I believe a similar idea was originally introduced with either Arduin or Tekumel (I haven’t read either yet, but vaguely recall someone mentioning that on a forum). Personally, I don’t think I would like to re-roll hit dice (and with variable dice type to boot) for every combat, but the idea of re-rolling hit dice per-level or per-session is intriguing. And it means that you might catch Cthulu on an off day (though one might argue the same thing could be achieved with less overhead by just rolling hit dice, as you could still roll all ones). I think there may be a typo in the dice conventions table lookup example. A minor issue, but still unfortunate given that I can see this section being confusing to some.

Conclusion

This is a fantastic book, and a fantastic toolbox for classic D&D. It is perhaps the most aesthetically attractive book in my RPG collection. Oh, and did I mention the art? It is wonderful. All by Rich Longmore. I like the unity. This is art direction done well. Like the Planescape of Tony DiTerlizzi (which is a setting that I have come to not particularly care for, though I still adore it for the art). I didn’t expect this, but I find myself wanting to run Carcosa out of the book, no house rules, completely on its own merits (I had planned on just using it as a toolbox).

Another Old Raistlin Picture

On Purity

I also roll my eyes whenever anybody talks about “pure OD&D.”

OD&D was about as pure as a backalley sleeper. It doesn’t borrow from other genres, it follows other genres into alleys and mugs them and goes through their pockets for loose ideas.

— Michael Mornard, on the OD&D Discussion forums