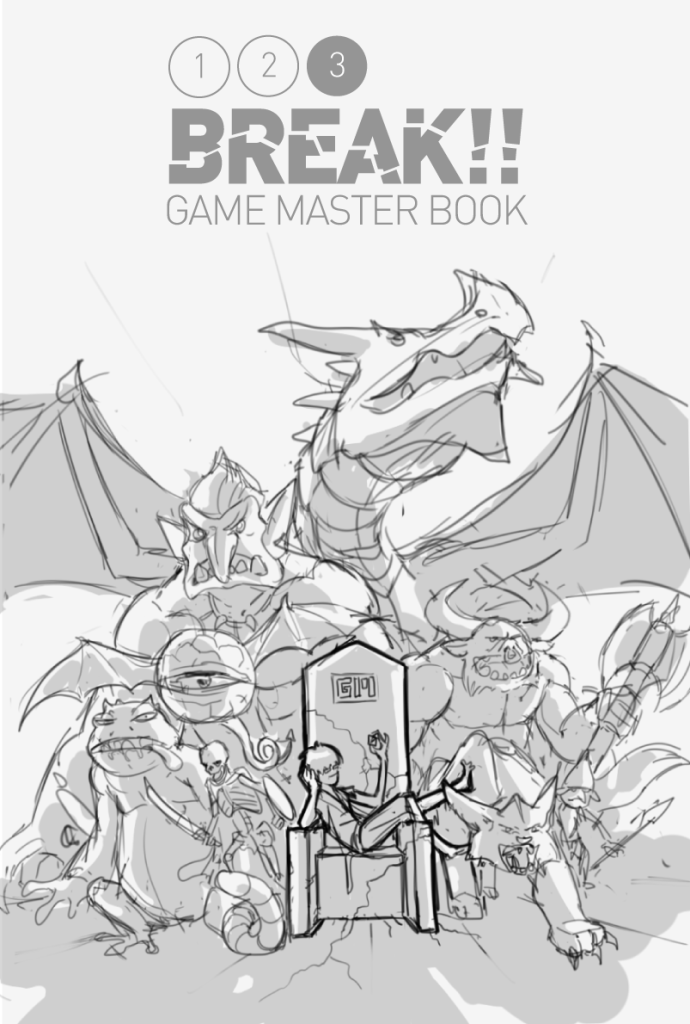

Compassionate Guardian in repose (source)

The demon hunters believe that their order was founded by a great philosopher who, by sheer insight and force of will, yoked the power of cosmic law to civilization. Above all, this philosopher saw the danger that elder chaos posed to the young tribes of humans. The founder’s insight transcended mortality, but his or her compassion was so great that final enlightenment (escape from the cycle of rebirth) was deferred, and instead the great presence remained lodged in a bronze statue. From this statue, the first generation of demon hunters was instructed. This was the first Guardian, though many others have since arrived, animated by other compassionate spirits. Guardians are usually made of stone or metal, and are rarely less than the height of two men. They may have supplementary limbs or multiple faces. Sometimes they radiate light or heat. Each guardian is unique.

The actions of a Compassionate Guardian are totally unpredictable. Sometimes, they remain inert, statue-like, for years, before animating without warning to destroy some lurking threat, though they never intervene in mundane political struggles. Most Guardians do not speak, though some will project thoughts into nearby supplicants or provide oracles in various ways. Those who revere the Guardians believe that Guardian actions flow directly from perfect enlightenment and are thus above any worldly reproach.

Though the Guardians are immensely powerful, they are occasionally overcome by the powers of chaos and destroyed. The remnants of a Guardian are considered to be relics, and prized by demon hunters and the superstitious, who believe that even the smallest fragment will bring good luck (and, sometimes, relics do have more direct powers, which may only be used by those on the compassionate path, which includes demon hunters, paladins, and those with backgrounds related to religious training, assuming continued devoutness). Sometimes, a Compassionate Guardian will crumble for seemingly no reason at all. Though this is rarely a joyous occasion, it is considered part of the great cycle of rebirth. As Guardians are assumed to be sacrificing their own ascension for the benefit of others, they are entitled to resume transcendence beyond material existence at any point.

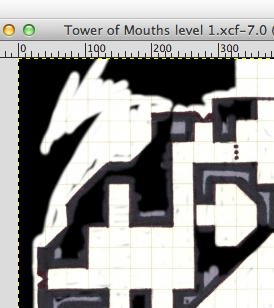

Demon hunters draw their powers from Compassionate Guardians, and thus must be within proximity of a guardian (or a relic), in order to cast Demon Hunter spells. For this reason, most demon hunters carry a relic at all times (this could be something like a small bit of metal on a leather cord or a stone fist mounted atop a staff). The greatest demon hunters carry weapons bestowed directly by a Compassionate Guardian, and such Guardian weapons function as relics. Even the weakest Guardian projects demon-killing power over a radius of many leagues, but the radii differs based on the guardian, and does not penetrate into the subterranean realms. Demon hunters will be able to sense if they are venturing outside the area of a Guardian’s attention, but this will not generally be a problem as long as the demon hunter possesses a relic. All demon hunters begin with a minor relic at the start of play, which is considered insignificant for encumbrance purposes and may be described in any way desired, either separate or integrated into another piece of equipment (for example, a stone Guardian eye mounted as a helm device).

In addition to the basic Compassionate Guardian ability to confer spells upon demon hunters, many individual Guardians can also grant more specific boons, or are known for particular concerns. For example, the legendary six-armed stone Guardian Varthamadeva is said to have granted a radiant blessing upon the weapons of any who would bring the remains of the living dead to her temple. She was also said to have transformed such remains into pure sugar crystals, after releasing the corrupted souls back into the cycle of natural rebirth.

The Iron God is said to be one of these Compassionate Guardians by some, though by no means do all share in the beliefs of the demon hunters.

This sort of ended up being an answer to Jeff’s first question, What is the deal with my cleric’s religion?