What are the most influential works of adventure fantasy? If you consider, somewhat arbitrarily, the last 10 years, I suspect the list would be something like The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, and Game of Thrones—all due to Hollywood and television. Recently, I was thinking about Game of Thrones, and how it seems in many ways to lie apart from other influential works of fantasy, despite sharing tropes both in terms of content—dragons, sorcery, undead—and narrative—sword fights, heroism, prophecy. So what distinguishes Game of Thrones? The Lord of the Rings is an epic fantasy, but also updates the medieval form of tapestry romance1. The Harry Potter stories have many epic fantasy elements, drawing as well from coming-of-age Bildungsroman and mystery traditions. Acknowledging the futility of thinking about genre in terms of essences, Game of Thrones still seems to wander alone; I think this is because it draws more from a different major narrative tradition.

Game of Thrones is cynical regarding human nature, grim in aspect, and employs a soap opera chronicle, but none of these elements seem to account for the difference in feeling. Most works of fantasy live primarily within the narrative traditions of epic and romance. Game of Thrones, however, works more like a tragedy; the fantastic elements occasionally take center stage, such as with the dragons or the fight against the Night King, but then fade, with less influence on the broader story. Examining the patterns, the core conflict in the story is basically Shakespeare’s Wars of the Roses cycle (the eight play sequence of Richard II through Richard III), with the ending and ultimate theme of Julius Caesar—sic semper tyrannis. If the ending is unsatisfying, I think that is due to the joining of these disparate elements. People expecting the satisfying reveals and perpetual curiosity of a well-crafted soap opera were betrayed by the political moralism of the Caesar ending; adventure and heroism are taken up and discarded with little sense of cosmic resolution or advancement.

The epic tradition generally celebrates the deeds of a hero, possibly as prototype for a nation, such as the Aeneid (for classical Rome) and the Kalevala (for Finland), or a culture, such as, arguably, The Lord of the Rings (the Shire as preindustrial England). The traditions of epic, romance, and myth fit together more comfortably, compared to soap opera and tragedy. In terms of popular culture, Game of Thrones was one of the biggest shows in the US of 2018, number three after Big Bang Theory and Roseanne2. The rest of the top 10 are all sit coms, procedural dramas, and talent shows. This ranking is America-specific, but the popularity looks similar cross-culturally. For example, Game of Thrones is popular in China3, South America, and Europe4. Game of Thrones will probably shape for a long time how people everywhere think about fantasy.

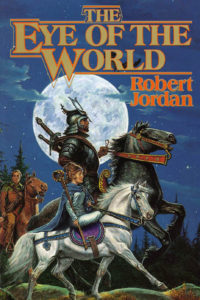

I used to enjoy The Wheel of Time, another extended fantasy epic, though I never got past book seven, as at some point I made a personal rule to avoid unfinished multi-volume works of fantasy. After thinking about this, I was curious what my reaction now would be to Jordan, so I read the first part of The Eye of the World, book one in The Wheel of Time. One thing that strikes me now is the generic feeling of many aspects of the setting, common fantasy tropes through a lens of Americanisms, though presented with consistency using invented vernacular and mythic resonance, mostly with Christian apocalyptic eschatology. I also wonder how I could have seen Jordan’s story as so distinct. The first third of The Eye of the World shows a sorceress who comes to protect a farm boy of cosmic significance, pursued by riders in black sent by the Dark One. Apart from some minor variations, this basically recapitulates the first part of The Fellowship of the Ring, and even back then I had already read The Lord of the Rings. I mean this more as description than negative evaluation—there are many worse things than echoing an effective narrative structure.

Part of Tolkien’s triumph was to make as few concessions to the modern taste for realism in narrative as was necessary to entice contemporary readers. Game of Thrones goes exactly the opposite direction; the aspects that hang together best make up the chronicle of who sleeps together and who gets betrayed or defeated. Sex and gangsters. So the realist mode of political struggle replaces the mythic cycle. Martin manages to avoid the bore of speculative fiction using magic as technology substitute; the magic and mythic backdrop of his setting is wondrous and compelling—winter is coming, the queen of dragons, and so forth. But none of that really seems to matter much in the end, which is more concerned with the Machiavellian heart of darkness. Realpolitik maneuverings could provide the basis for a game, but it seems like such a game would be far from the picaresque pleasures of discovering Vance’s Dying Earth or delving into Moria on the way to fulfill a mythic quest.

1. Thomson, G. (1967). “The Lord of the Rings”: The Novel as Traditional Romance. Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature, 8(1), 43-59. ↩

2. https://www.businessinsider.com/game-of-thrones-compared-to-most-popular-tv-shows-of-2018-ratings-2019-4#8-americas-got-talent-tuesdays-nbc-2 ↩

3. https://daxueconsulting.com/game-of-thrones-china/ ↩

4. https://variety.com/2017/film/global/game-of-thrones-overseas-plaudits-ratings-1202541767/ ↩