JB has a post up about how the traditional D&D magic-user class sucks. I’m not putting words in his mouth, either:

So when I say, MAGIC-USERS SUCK, I’m only talking about the magic-using class, as used by player characters. And my astute observation (that they suck) comes from a careful review of the rules as written and their actual use in-play. My concern is about the “fun factor” of the class, both for the player who actually plays the character, the other players in the party, and the DM running the adventure.

In contrast, I think the magic-user as written is great, one spell slot at first level and all. First I’ll tell you why, and then I’ll address a few of the points he raises directly.

Eknuv the magic-user, tamer of hobgoblins

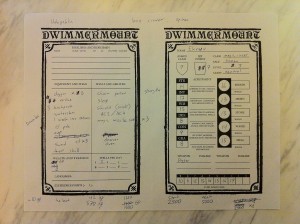

This morning I played a magic-user in Dwimmermount at OSRCon, and never once did I feel like I had nothing to do. We started at second level, but this still only gave me two prepared first level spells, a scroll, and two hit dice (which was 5 HP, as it turned out). Still in danger of being killed in one hit. I had AC 9, two daggers, and a small collection of adventuring gear. I had sleep, charm person, and a scroll of shield (which I never used). The sleep got us past a group of hobgoblins, and the charm person got me a hobgoblin henchman. But I didn’t feel the need to use any spells until fairly deep into the dungeon, on the second level.

Let’s also look at the list of first level spells. I’ll stick to the 3 LBBs here, because I think they encapsulate the essence of the class best. Later editions dilute the list by adding direct damage spells like magic missile too early, but the essence still remains if you look.

- detect magic

- hold portal

- read magic

- read languages

- protection from evil

- light

- charm person

- sleep

All of these spells are solutions to common dungeon problems. Detect magic can tell you which treasure is most valuable, or what aspect of a complex puzzle you should focus on (or avoid). Read magic allows you to use scrolls that you find without needing to retreat to the surface or potentially identify some magic items, if there are inscriptions. Read languages allows you to decipher maps or clues (I wished that I would have memorized read languages today when I was exploring Dwimmermount). Protection from evil prevents enchanted monsters from getting near you (like level-draining undead). Light is a failsafe in case you lose your main light source, or need to light an area that can’t be well lighted by torches or lanterns (like under water, in within magical darkness). Charm person gets you a retainer. Sleep allows you to avoid one direct confrontation. You get one of these potential wildcards in addition to everything else you can do as a person with two arms, two legs, a brain, and exploration equipment.

How much of a character’s capabilities should be located in the class “extras” and how much should be player creativity and interaction with the environment? I see the second category as primary, and the first as secondary. Everyone is an adventurer. Fighters get a small advantage in terms of combat (a bit more HP, better weapon selection, etc); thieves can climb and have a small advantage in some dungeoneering activities; clerics get to turn undead (and no spell at first level!); magic-users get a spell and the ability to use magic items and scrolls.

Which brings us to scrolls. How could JB have forgotten to mention scrolls? Scrolls allow magic-users to carry a potentially limitless number of utility and attack spells. If using the Holmes rules, they can be scribed for 100 GP per spell level, and if not using those rules DMs can place them as treasure or make them available for purchase (doing so is part of the class design, not a house rule). Even more spectacularly, depending on your edition of choice, you may be able to cast spells above your level from a scroll (I believe AD&D gives a chance of failure, but OD&D and B/X allow magic-users to cast spells of any level if they are on a scroll). In addition to scrolls, there are, of course, other magic items, most of which cannot be used by any other class. Even a small amount of adventuring will provide a fledgling magic-user with plenty of resources and options.

Now to individual points. Quotes are from JB’s post linked above.

The existence of house rules in many, many campaigns to change or increase magic-user effectiveness.

People house-rule many things. The most common house-rule I have seen in TSR D&D (and its simulacra) is full HP at first level. This is something I don’t think is necessary, is usually not specific to the magic-user, and even if implemented still leaves the magic-user often dead after one hit.

The modification and tweaking of the class and its abilities over-time and across editions, expressing dissatisfaction with the class as conceived in prior/earlier editions.

This has happened to all the classes, not just the magic-user. The humble fighter has probably come in for the most revision (due to some people not liking the lack of “awesome things to do” written on the character sheet), but every single class has been targeted at one time or another. The thief takes away skills from other characters, the cleric is a healbot, or is out of place in swords & sorcery settings, etc, etc. I do play commonly with several house rules about weapons and armor, but this is because I don’t care for weapons restrictions in general, not because I think that the magic-user class needs more weapons. Also, the OD&D method of using d6 for both hit dice and damage solves the same problem.

Instead, they’ll be skulking around the back of the pack, or whining that they need to retreat the dungeon to re-memorize their sleep spell(s), or bitterly complaining that they “can’t do anything.” Or all of the above.

Retreat is a strategy that is often available to PCs. There is nothing wrong with this; it will have advantages and disadvantages like any other choice. I don’t understand the complaint about the 15 minute workday. By all means, retreat if you think it will benefit you! This is only a problem if you have a planned sequence of events that your players must experience in order. Also, can’t do anything? How about holding the light source, flinging oil, reloading missile weapons, or any number of other helpful things?

Another house rule I often use is to give magic-users a chance to retain spells after casting them by succeeding at a save versus spells. But the same house-rule also provides for spell fumbles if you roll a 1 on the save (the point was not to give the magic-user more utility, but to make magic less reliable and more flavorful).