You Died is a book about Dark Souls, written by a pair of game journalists. It was first published as a simple paperback and then reimagined as a deluxe hardcover funded by a Kickstarter campaign. The book is printed offset in Italy on 140gsm Magno Natural uncoated paper and plentifully illustrated. In keeping with the profession of the authors, many of the chapters have a journalistic flavor, describing the origin of Dark Souls and vignettes about its reception, often via experiences reporting about the game. However, the book also includes thoughtful chapters on game design, player motivation, and creative influences. The chapters alternate through essays, brief discussions of locations within the game, and there is a brief appendix discussing the setting and important characters. This book was clearly a labor of love, attested by the attention paid to sturdy construction, the careful design, and the reverential art direction. I think it should be obvious that the text itself will contain many spoilers, but I think I have kept this post free of spoilers.

Let’s get the discussion of weaknesses out of the way. While the binding and cover are excellent, the black inks could have greater depth, and this is especially noticeable on the pages with white text on black background. In keeping with the celebratory aspect of the work, occasionally the prose shifts into a sentimental register noticeable even to me as a fan of the game. Jason also has a penchant for punchy wordplay, which I suspect works slightly better in short form web writing compared to a longer text (sample chapter titles: You’ve Got Chainmail, Knight & Subscribe). Along similar lines, while the layout is excellent in general, there are a few flourishes that would be more at home in a magazine or web site, such as the occasional pull quote. Honestly though, taken in perspective, these are all minor issues. The book as a whole is an impressive accomplishment; as a physical artifact, as a thoughtful discussion of game design, and as a consideration of the play culture around Dark Souls.

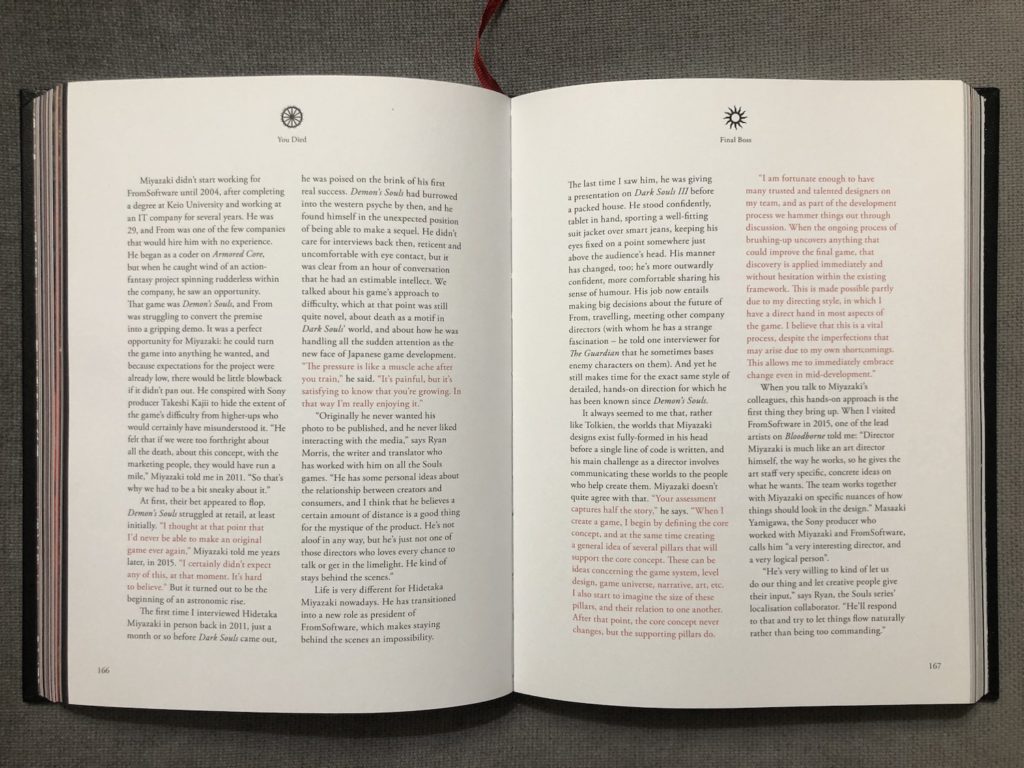

I enjoyed all the chapters, even the human interest features which tell stories about the importance of Dark Souls to various individuals, but my favorite parts were the interviews with Hidetaka Miyazaki, the game’s director, whose words are rubricated within the text. Just about everything Miyazaki says is revealing or insightful in some way, but I will highlight two quotes as examples. The first is about respecting the accomplishments of players, even those that might be considered exploits:

During lunch with Hidetaka Miyazaki in London in April 2012, I asked him if his team had designed that … spot especially for grinding. He assured me they hadn’t, but since players had discovered on their own how to manipulate it for their gain, he didn’t want to patch the AI behaviour and steal away something that now belonged to the community.

You Died, p. 60

The second is about the interplay between exploration and ambiguity in design:

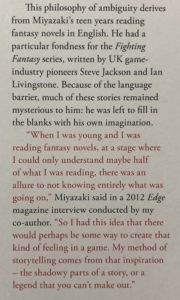

This philosophy of ambiguity derives from Miyazaki’s teen years reading fantasy novels in English. He had a particular fondness for the Fighting Fantasy series, written by UK game-industry pioneers Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone. Because of the language barrier, much of these stories remained mysterious to him: he was left to fill in the blanks with his own imagination.

You Died, p. 311

Considering 1974 D&D, there is a case to be made that slightly incomplete rules prompt (or demand) some degree of customization or finishing on the part of the referee. While this might be a flaw for some purposes, it also creates a degree of investment and uniqueness in the realized game. There is also the more general idea that a void can be fruitful. The ambiguity and obscurity of what is ultimately going on in Dark Souls works similarly, creating both curiosity about the details scattered throughout the game (encouraging exploration) while also creating a space for the player’s own idiosyncratic interpretation, given weight and shape by extensive mythological symbolism.

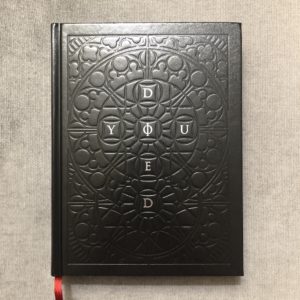

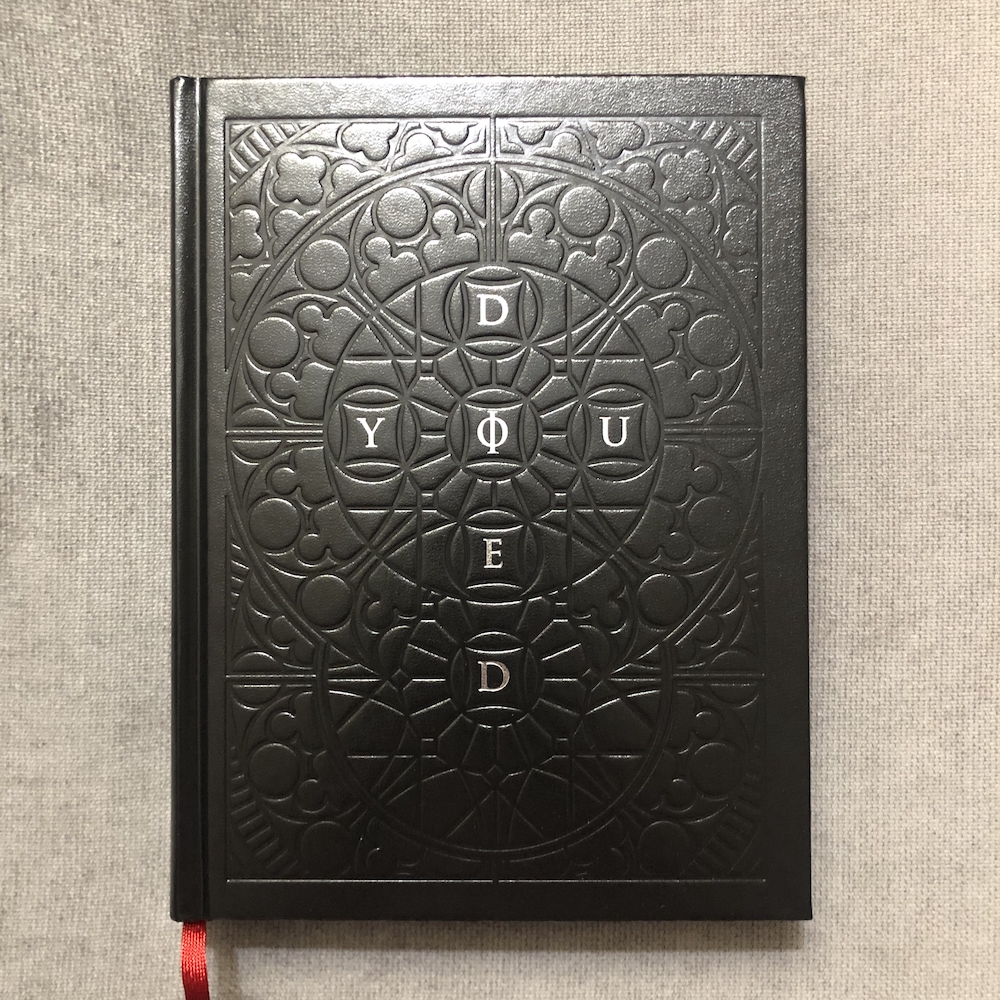

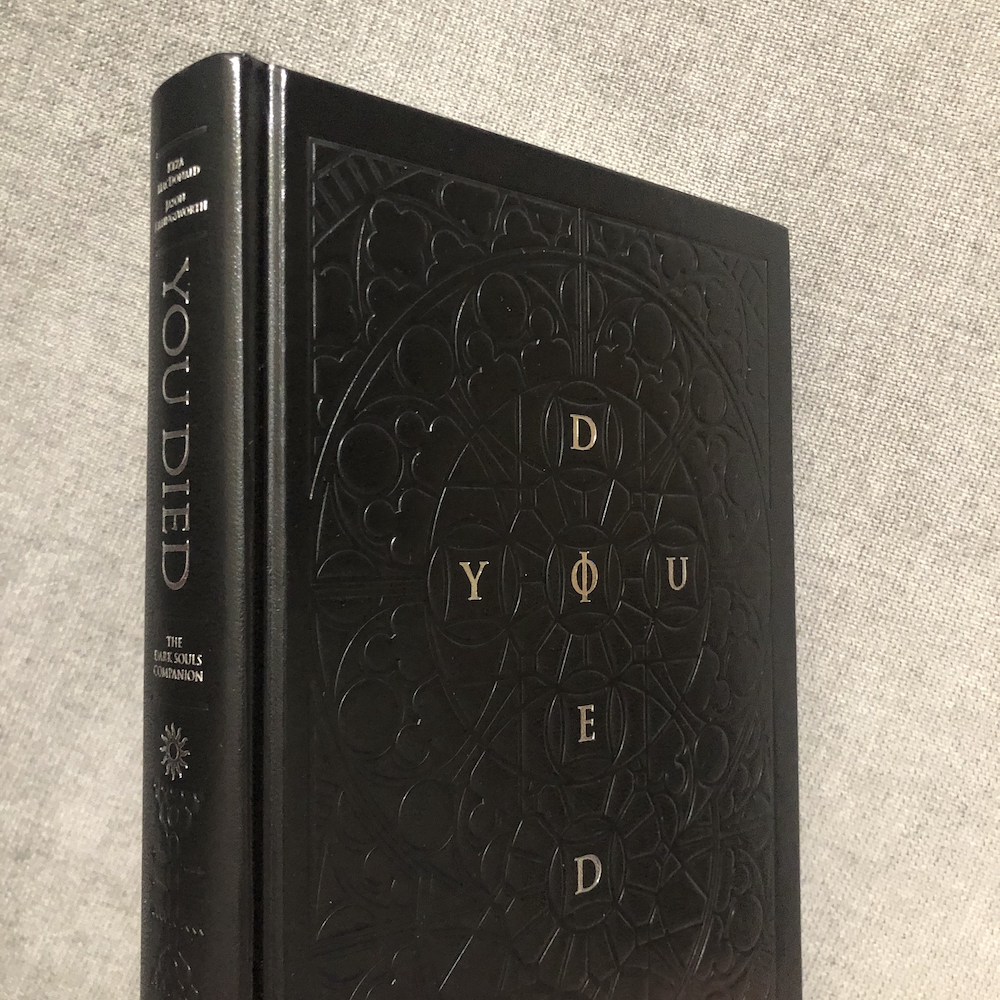

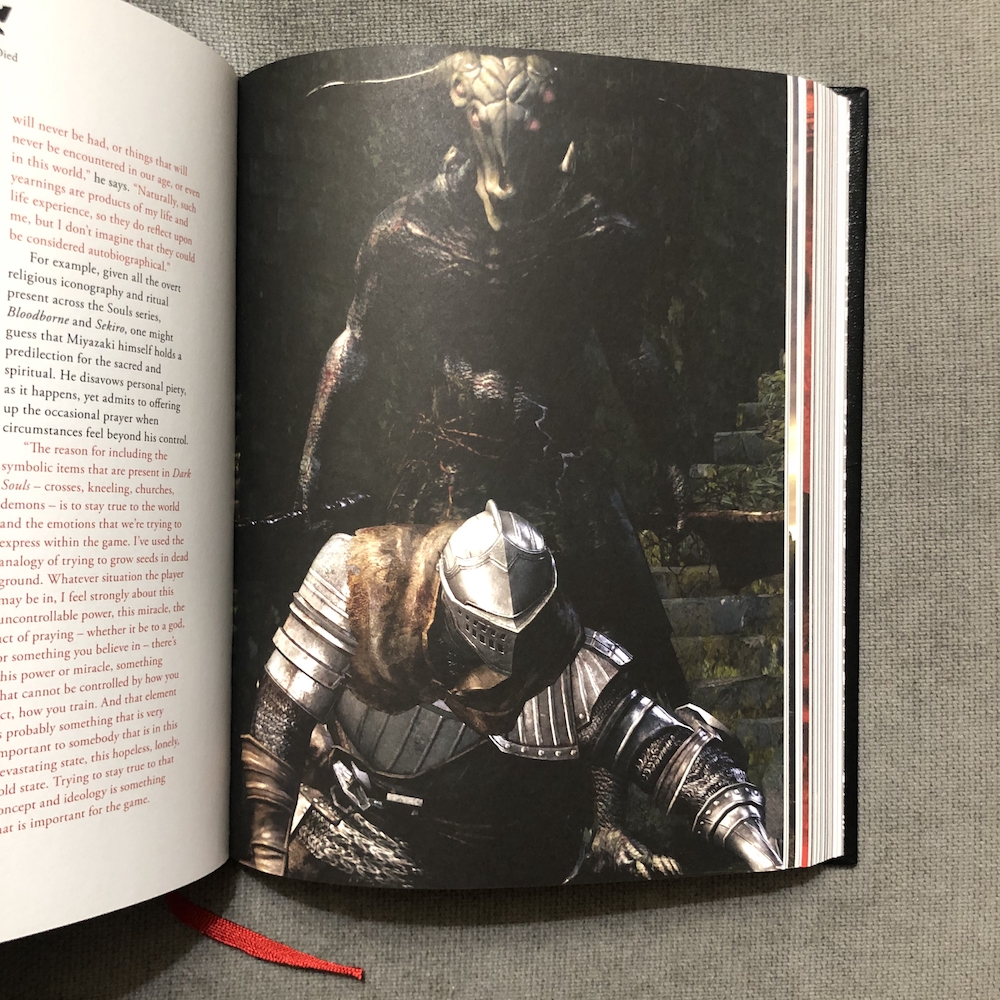

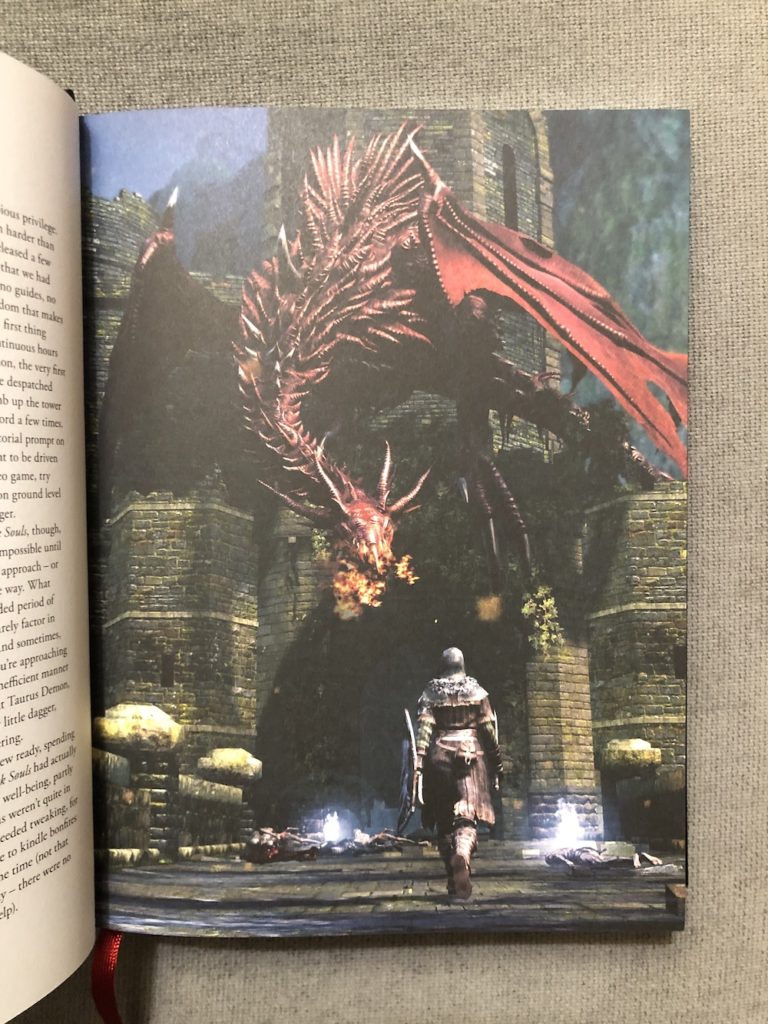

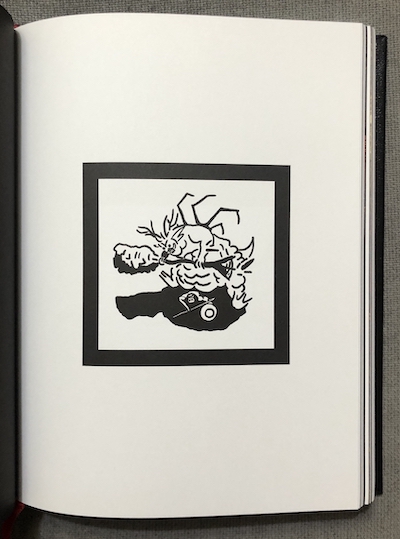

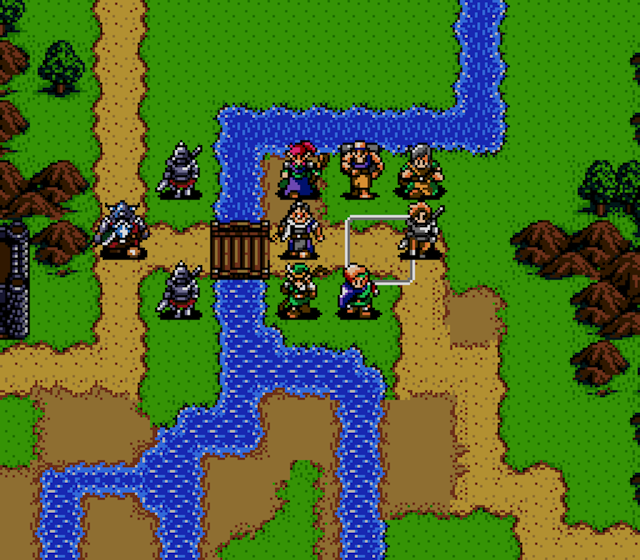

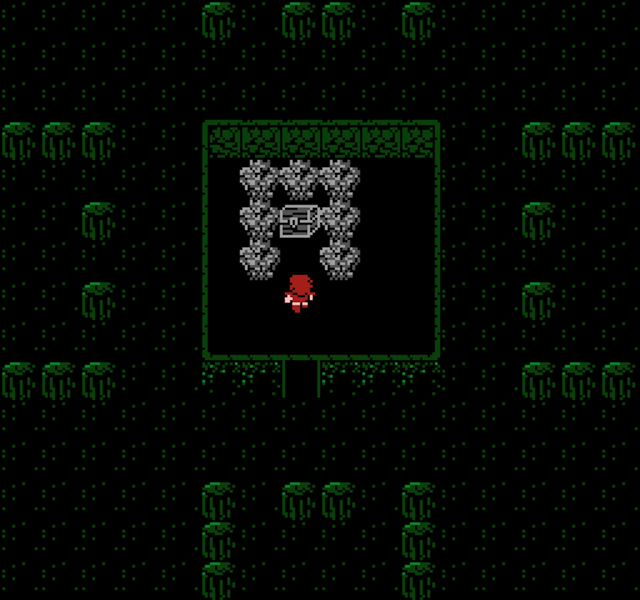

The illustrations are a mix of digital pieces, which I think might be processed photos of actual gameplay, small sketches placed at chapter headings, and whimsical line drawings skillfully caricaturing various experiences of gameplay that will immediately be recognizable to longtime players. These small line drawings especially work to soften the seriousness of the text both in terms of the bleak themes running through Dark Souls the game and the risk of pomposity inherent in giving a book of game journalism such fancy clothes. This is in keeping with the tone of Dark Souls itself, which breaks the somberness with occasional levity. The book is adorned with religious imagery, such as the blind stamped cathedral window cover motif and the title lettering in the form of a cross, not to mention the aforementioned rubrication. The book looks and feels like a psalter from the outside given the cover design, ribbon marker, and gilt page edges. It is no exaggeration to say that obsession runs through the project and text. I know, because I recognize aspects of my own interest reflected back to me. But, like the caricatures throughout, the text is self-aware, and pays respect to the game without taking itself too seriously, most of the time.

As noted above, the book does contain some spoilers, including a few details I have missed in my own playing so far, and some of these made me curious about the online play component, which I have so far totally avoided, being primarily interested in exploring the worlds of Dark Souls on my own terms and through the interfaces the game provides. In a similar vein, apart from occasionally browsing Fashion Souls, and reading a handful of guides about what stats to level or how weapon upgrades work, my primary social engagement about Dark Souls has been limited to discussions with a small coven of Google Plus exiles that I met playing old school D&D and related hacks. Now I am more curious about some of the other culture and cottage industry that has accreted around the game, such as VaatiVidya’s YouTube videos interpreting the morsels of setting detail or the “Kay Plays” of Dark Souls, which chronicles the journey of a novice through the game.

Though I suspect the writing would be engaging for someone who is interested in video games or game design more generally but has minimal experience with Dark Souls, some of the references are obscure and others might seem trivial without the echoes of personal game experiences. You Died is first and foremost a scripture for those initiated in the tribe. Praise the sun! Or the dark, as per appropriate allegiances.

I will close with some additional details for fellow book nerds. When I emailed Jason to ask a few questions about the book’s construction (yes, the binding is stitched), along with answering my questions he sent back links to several videos of the production process:

And here is a photo of the red letter treatment:

More About the Publisher

- https://www.tuneandfairweather.com/

- https://www.instagram.com/tuneandfairweather/

- https://twitter.com/tuneandfair

Purchase Info

- Order Date: 2020-12-16

- Price: $127.00 CAD + $31.56 CAD shipping = $158.56 CAD total (approximately $125 USD including shipping)

- Details: You Died deluxe hardcover (note: I think I ordered the cloth-bound edition but it looks like I received the Skivertex simulated leather edition, which would be a small upgrade)

See here for my approach to reviews and why I share this purchase info.