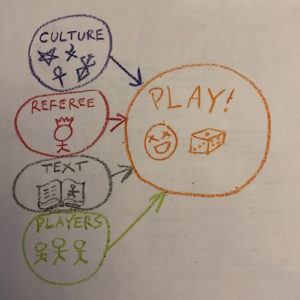

A longstanding fault line in thinking about the design of tabletop roleplaying games is belief about the influence of system on resulting play experience. The System Does Matter manifesto, and other discussion centered on the Forge forum, argued that game designers could shape play experience systematically by focusing their design on theoretical concerns, communicated to players through language in game texts. Though this approach has undoubtedly influenced mainstream and niche games, the most successful games remain stubbornly unfocused and the experience of play using a given system seems highly variable. Considering the approaches different schools of psychology take can help provide an explanation. Both game design and game facilitation are, after all, forms of applied psychology. Particularly, it seems to me that the various influences on resulting play can be understood as play culture, referee, text, and player engagement.

For my purposes, a rule is a procedure that guides play. Guidance can either call for player behavior, such as to roll a twenty-sided die at a particular time, or clarify some aspect of the shared fiction players collectively imagine, such as whether a monster falls into a pit. A system is the collection of rules that players endorse and use, either by heuristic (“it is in the book”) or explicit. It is impossible for any system to completely determine the experience of play in the same way that it is impossible for a legal code to completely determine the behavior of people in a state. Similarly, the system must have some effect on the experience of play if players ever look to the rules for guidance regarding appropriate behavior or to determine the state of shared imagination.

The influences described above break down into causes involving culture, individual people, and situations. The effects of referees and player engagement are both influences of individuals. The referee, for games that have such a role, tends to be comparatively more influential between these two factors, even though the number of players is usually greater, as the referee has more wide-ranging responsibilities for facilitating the play experience.

Personality psychology studies the influence of stable individual differences on psychological outcomes. For example, a referee that can do entertaining voices will likely bring this ability to any game they facilitate, from D&D to Dark Heresy. Referee preference for extensive preparation is another example of referee individual difference affecting play experience. Presumably, many more general personality differences, such as extraversion and optimism, will also affect the play experience systematically.

Social psychology studies the influence of situations on psychological outcomes. Incentives, norms, and goal cues are examples of ways situations can influence psychological outcomes. In the roleplaying context, the structure of experience point rewards is a situation effect. Game texts, and other table paraphernalia such as maps, are features of the situation in these terms. Every time players look to the text, the situation affects the play experience. It is worth noting that texts are made up of more than language, also including art, layout choices, and so forth.

Play culture differs from situation in, among other ways, that culture is more diffuse, less immediate, and more persistent. A group can run a B/X D&D game for some time and then start a new Call of Cthulhu game. This changes an aspect of the system, but may affect play culture minimally. It is possible for people to move between cultures, such as when a person moves from a family context with particular ethnic assumptions into an institutional culture, such as school or a company office, but it is generally harder to move between cultures than it is to affect situations. Unlike situations, cultural influence generally requires socialization, distinct symbol systems, and deeper, often unexamined, assumptions1.

The ranking of influences presented above helps explain the diversity of play experiences. For example, in one play culture, Burning Wheel is a comedy engine. In another, it is a genre emulator. In one play culture, Pathfinder is a carefully tuned tactical teamwork engine. In another, it is a competitive exercise in character optimization. The Pathfinder Core rules explain some shared variability in the play experience, such as how numerical character ratings affect aspects of the shared imagination. This kind of character has a greater chance of hitting in combat than that kind of character. This monster will behave in a particular way if player characters take certain actions. However, the play culture shapes when and how elements of system take the stage. To accept this neither dethrones the influence of system nor casts players as pawns of innumerable, clever system nudges.

This way of thinking about games leads to several conclusions. First, the play culture likely shapes play experience disproportionately because the influence is less immediately visible. This is why dropping into a group using ostensibly the same rules can feel so disorienting. Consider the slightly stylized example of a fifth edition D&D game using Curse of Strahd in the mainstream game store play culture compared to a fifth edition D&D hex crawl in an OSR culture expecting emergent narrative and diegetic problem solving. Similarly, groups participating in the mainstream Pathfinder play culture are likely more similar than different, in terms of play experience. Participating in a Dragonsfoot-style Grognard culture, whether running AD&D or some other set of rules, probably leads to a more similar play experience than looking at the AD&D text independently, as a primary source of system, or the particular referee. This suggests that roleplaying game designers should pay more attention to exploring and understanding play cultures if the goal is to affect the experience of play.

For statistics nerds

Y = Xculture + Xreferee + Zsystem + Xtext + Xplayers + ε1

Zsystem = Xculture + Xreferee + Xtext + Xplayers + ε2

Where Y is play experience.

In the figure below, I have highlighted the effects that I think are particularly important:

There are probably some edge cases, which would show up as error in the above model.

Alternative models

Referee primacy

Y = Xreferee + Xplayers + ε

This is play experience being primarily determined by group (coordinated by referee), as argued in Robin’s Laws of Good Game Mastering (2002):

What really makes a difference in the success or failure of a roleplaying session is you [the referee] … Our biggest task as GMs is to direct and shape individual preferences into an experience that is more than the sum of its parts.

GNS

Y = (Xsystem × Xplayers) + ε

GNS (gamism/narrativism/simulationism) hypothesizes a fit effect interaction between system type and player priority. The System Does Matter article is from 2004.

PIG-PIP

Y = Xparticipants + ε

The 2018 PIG-PIP formulation (Participants Invent Games-Participants Includes Paraphernalia) gives system a metaphorical seat at the table:

7. The Basic PIG-PIP Claim: Participants determine the character and quality of a game experience. In addition to the players and GM, “participants” includes paraphernalia used during the game and preparation for the game–game texts, house rules, miniatures, tables, chairs, the physical or virtual space the game is played in, snacks, etc.

1. I am mostly ignoring cognitive psychology. Though it is one of the major schools of psychology, it seems less relevant to the play experience of tabletop roleplaying games. This could be a bias on my part. However, the minimal influence of cognitive psychology on tabletop play experience seems like a key way in which tabletop roleplaying games differ from the more passive, less creative experiences evoked by video games and audience media such as movies and novels. ↩

This explains my high school gaming group where I would constantly be changing games to find one that work and the results were always kind of shoddy. It was simply a matter of the right cultural components not being there.

I don’t think GNS or any of the later iterations built off that theory (e.g. Ron’s Big Model) think of the system and players as being separate effects, or of referee and players as having separate effects. When I read it, I see it as more of an argument of coherency – that what the referees and the players are all ‘players’ of some sort and should all be on the same page with regards to what the game should be, and the system should align with that intent, so as little time or energy is wasted on stuff that isn’t the main intent. At the time, in the late 1990’s/early 2000’s, this was very important because many games promised what Ron described and called narrativism, but few games reliably delivered it. (Thus, figuring out how to focus on the bare essentials to allow for a maximally narrativistic play became a model for many Forge-descended games – this is very evident in Mountain Witch or Primetime Adventures.)

I guess I am just trying to say that its important to keep in mind that the historical context of GNS is that it was developed at a time when the most popular RPGs, or at last those most abundant at bookstores, were often written by people who didn’t seem to understand what intended play was supposed to look like, and often made claims about play that could not be borne out in play without social constructs that weren’t put into the rules. I think some of that originated from people thinking there was only one ‘real’ way to play RPGs, and although different designers used very similar words to describe what that play was, I think the sort of critical evaluation of rules texts that Ron argued for showed that different designers were actually intending for wildly different games to arise from RPGs. My sense is that people are a lot more cognizant now, 15 years later, about the need for game design to be explicit about the sort of gameplay the designer is envisioning. Its a lot healthier!

Of course the shared sense of play between players, which how I think of the element you refer to as the culture, will always have an overriding affect on what play time actually consists of – but I’m just not able to seperate that from the players themselves and their motivations. Players (both the referee and the others, whatever we call those roles) have soem assortment of motivations and intentions for what they want out of game play – they may not be a coherent set of motivations, even an individual’s motivations might not be coherent. A group’s motivation for play might differ greatly across time, or with even small changes to who the participants are. But if rules cannot channel those motivations, help unify them and help emphasize the things those players want from game play… if rules don’t matter, then what is the point of game design? I think rules do matter – how much they matter though is maybe itself a variable that differs across different gaming groups.

Anyway, these are my scattered thoughts from reading your post. My computer froze halfway through writing this up and I was able to recover a portion of what I’d written, so I apologize if there are any missing threads of logic or incomplete thoughts.

-Dave

PS: I really like your path analyses. Doing much causation statistics lately?

In my experience, the system had little importance while the people involved had much.

I played Paranoia a couple times in ’93. I didn’t understand anything about the rules because I wasn’t allowed to read the book (and my English was not very good at the time, anyway). But it was fun and I really liked it. I, who come from a Socialist/Communist family, didn’t take offence that the Comms were the bad guys. It was an American game, let’s have fun.

In ’96 I refereed AD&D (a mix of 2e and 1) and the party never finished their first adventure because everyone were arguing that I was doing it wrong (for different reasons) as a DM, it was a bad gaming experience because nobody (other than me) had read the books but everyone had read (epic) fantasy novels and watched (epic) fantasy movies and thought the rules should allow them to be superheroes and attack three times with two swords and then dodge when the enemy attacked back and stuff like that.

Two years after, with the boom of Vampire the Masquerade, I tried to narrate a campaign for the same groups, again only me having read the manual, and the adventure never progressed because they thought the rules of the vampire society were the rules of the game (example: they asked the Prince to prosecute a criminal, they though the rules of the game forced the Prince to act as they expected, they didn’t acknowledge that the rules of the society can be broken by corrupt politicians just like in real life).

I never played games with the same guys. They were all morons pretending to know when they were clearly ignorant (they didn’t read the damn manuals!)

I was part of a years long campaign of Werewolf/Mage with a Storyteller who never asked us to roll dice. The games was not exactly larp, we didn’t wear costumes or pretended to be werewolves and magicians. Some players acted in character, some (like me) played in a mix third/first person (“my character looks for a phone booth” or “I look for a phone booth”). The Storyteller always told us if we succeeded or failed, and nobody questioned his word because the adventures were great, the story was great, our characters were important and our actions had evident consequences. It’s been the best experience I have had playing RPGs.

I started running Call of Cthulhu but the published adventures and scenarios are boring and a chore to read an prepare and memorize and useless on the table (all the important bits hidden between walls of text). So I started writing my own one-shots. One shots are the perfect take for CoC, pretending you can defeat the old ones is mental wanking. But in Mexico, few people want to play games where they can’t be superheroes wielding oversized swords.

When 3e was released, I ran a few adventures with some friends. It was ok, but the system was a chore and doing math to know how much XP each deserved was boring, so I dropped that and started giving XP equal to the gold they acquired and the game got better for everyone, but then we graduated and the game stopped.

For years, I abandoned the RPG world until once day some guy trying to insult another guy said he should be playing OSR games. OSR was a bad thing in this exchange, and I wanted to know what this OSR thing was.

I found out. I now don’t play other than OSR games any more. I love them! People like them, as well.

Sorry, I digressed a lot. I just wanted to give my testimony and how to me (I am a Social Psychologist, by the way), the system is not the main thing, it’s the people, including the referee. The system has to support the referee, make his work enjoyable (not easy, writing CoC adventures is not easy, but it feels good). The system of the OSR games is easy. You learn one you understand everything.