Combat house rules are hard to remember in the heat of the moment, so these are designed to augment traditional B/X procedures. If players do not learn the options or forget to use them, the game will not be much harmed. Applying these procedures should help create the feel of Dark Souls tactics to the degree permitted by traditional tabletop RPG rules. The final playbooks will also include reminder cues to help players. I tried to keep new rules to the absolute minimum required to support basic Dark Souls actions.

For now, shields just grant the standard traditional +1 AC. A Dark Souls emulator deserves better than that, but I also do not want it to slow down combat or make adventurers too tough. I do not like rules that allow adventurers to sacrifice a shield to avoid a hit.

Starting Weapons

All playbooks provide an initial melee weapon proportional to starting strength. Some provide a missile weapon as well, proportional to initial dexterity. The instructions section of each playbook includes available initial weapon choices. See below for a compiled list of starting weapons.

Two-Handed Weapons

Adventurers with an ability score high enough to use a weapon may wield it one-handed. Some weapons may be used two-handed to deal extra damage. When using a melee weapon two-handed, roll two damage dice and take the larger result (that is, roll damage with advantage).

Dual-Wielding

Adventurers may wield a weapon in each hand, allowing two attacks per combat turn. However, dual-wielded weapons are limited by the lowest of both strength and dexterity. For example, an adventurer with strength 14 and dexterity 10 wielding two weapons may only use weapons that deal 1d6 damage or less. Further, dual-wielding prevents using a shield or any other off-hand item. When dual-wielding, both attacks must be rolled at once. Combatants may not save one attack for a potential parry (see below).

Critical Hits

When a critical hit occurs, players can choose to inflict either double or full damage. For double damage, roll the weapon die twice and then apply any other modifiers. For full damage, do not roll damage but rather use the highest potential result of the weapon die. For example, a critical hit with a longsword (a 1d10 weapon) will inflict either 2d10 or 10 base damage, according to the player’s choice. Natural 20s inflict critical hits, as do strong attacks, parrying counterattacks, and sneak attacks (see below).

Strong Attacks

Successful strong attacks are critical hits. However, strong attacks leave the attacker open to counterattack, reducing the attacker’s AC to 10 (unarmored) temporarily unless the strong attack reduces an enemy to zero hit points, in which case AC is unaffected. Because of this, strong attacks are best used finish off enemies. Reduced AC from a strong attack persists until the adventurer that made the strong attack acts again.

Parrying Counterattacks

Rather than attack, a combatant may try to parry and counterattack. This requires waiting for an opponent to attack. Resolve a parry with opposed attack rolls rather than static armor class. If the parry is successful, the combatant parrying inflicts a critical hit for taking advantage of an opponent’s opening. Parrying is only possible against opponents wielding weapons.

Sneak Attacks

Concealed adventurers may make sneak attacks with melee weapons. Sneak attacks are made with advantage and inflict critical hits. Melee weapons used for a sneak attack are limited by both strength and dexterity. For example, an adventurer with strength 14 and dexterity 12 may use weapons dealing 1d8 damage for a sneak attack. Following a sneak attack, successful or otherwise, make a dexterity check (with disadvantage if base AC is higher than 12) to determine if the adventurer remains concealed. Concealed combatants may not be targeted directly.

Blunt Weapons

Blunt weapons (for example, caestus, club, and mace) are more effective against some enemies but are also more clumsy than other weapons. Exactly what clumsy means must be ruled situationally by the referee but may include occurrences such as striking after an opponent with a more agile weapon.

Enchanting

(This upgrade system replaces the attack bonus rule described in the previous post.)

Upgrade weapons during downtime by bringing special resources, along with personal essence freely given, to a blacksmith or enchanter. Weapons may be improved up to +5 and can be infused with other magical powers. Enchantment bonuses apply only to attack rolls, not damage rolls. Elemental enchantments modify the type of damage inflicted and can sometimes augment amount of damage.

Special resources may be explicit external treasure but can also be harvested abstractly from defeated enemies according to the magical principle of similarity. For example, the essence of a monster that breathes fire would be useful for a fire enchantment. Record abstract essences in HD or level terms. Such monster essences do not occupy item slots.

The process of improving a weapon links it to the wielder’s soul. Because of this, the original wielder suffers any damage the current wielder takes, making it unwise to lend your enchanted weapon to another. (Yes, this means that stealing an enemy’s linked weapon and cutting yourself is a strategy. Good luck with that.) The improvement process uses the personal essence to create the link between living soul and item. Such personal essence can take many forms. For example, blood, hair, or valued secrets. The details of the essence affects the weapon’s physical manifestation.

Since enchanted items draw their power from living souls, such items rarely persist beyond the death of their original wielder. Rarely, a wielder’s power and personality are so strong that an enchantment is permanently burned into the item. Such legendary items are unique and sought after.

Bleeding

A bleeding combatant suffers one damage per combat turn. Bleeding is easily staunched after combat. Some weapons, such as katanas, cause bleeding.

Poison

Poison of the common variety inflicts one damage per dungeon turn and can only be cured by consuming an antidote. Uncommon and rare poisons may have other effects. Most poisons allow an initial constitution saving throw to completely resist the effect.

In game design terms, bleeding and poison are fast and slow hit point attrition effects.

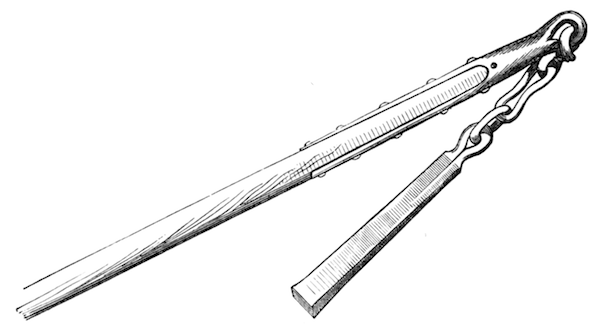

Melee Weapons

| 1d4 | caestus | dagger | broken straight sword |

|

|

|

|

| 1d6 | club | hand axe | short sword |

|

|

|

|

| 1d8 | broadsword | mace | scimitar |

|

|

|

|

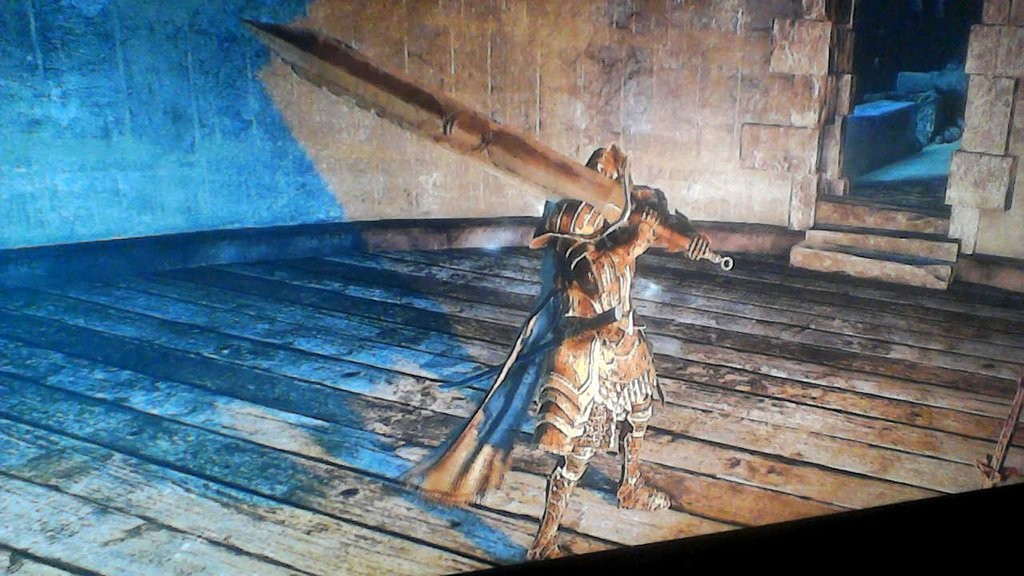

| 1d10 | battle axe | longsword | spear |

|

|

|

|

| 1d12 | bastard sword | greataxe | halberd |

|

|

|

Missile Weapons

| 1d6 | shortbow | light crossbow |

|

|

|

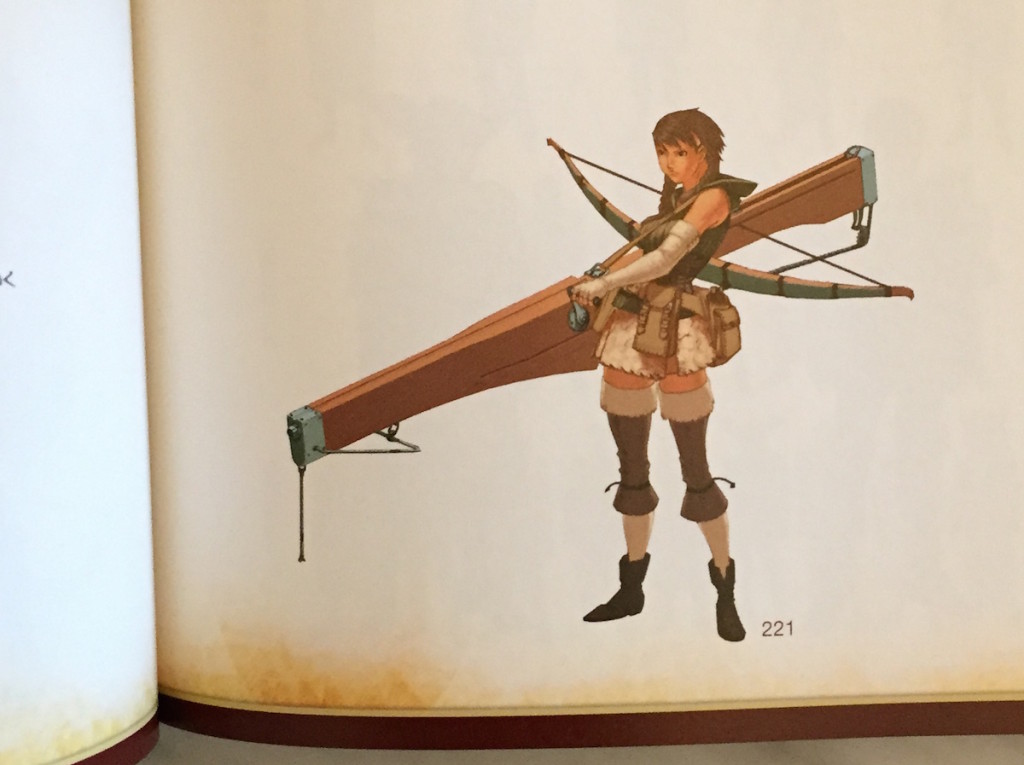

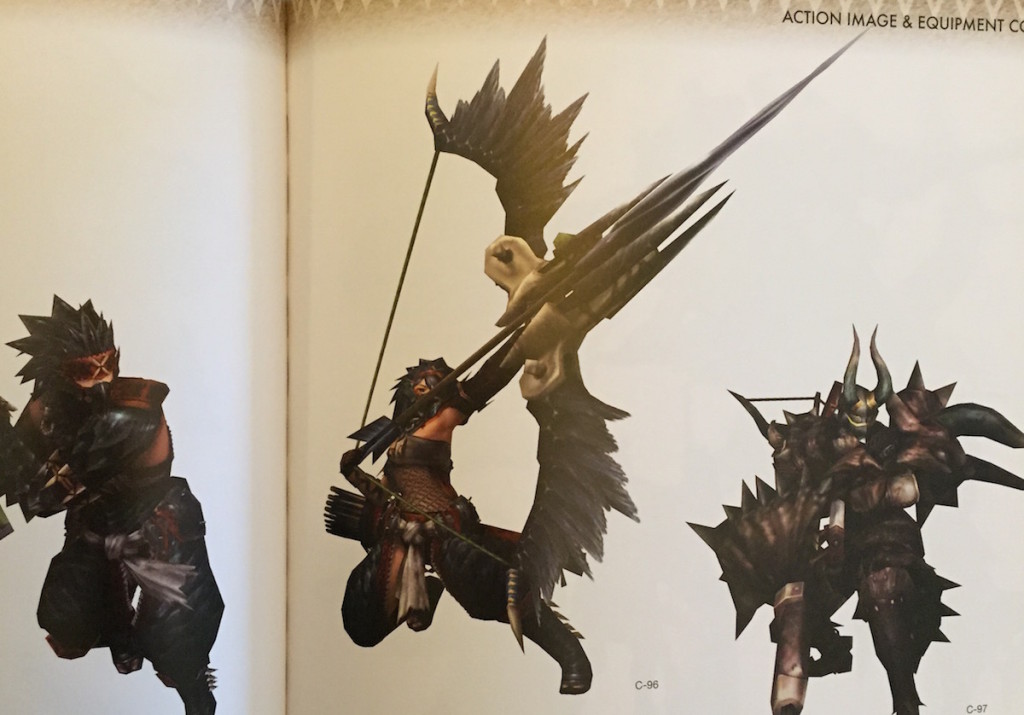

| 1d8 | longbow | heavy crossbow |

|

|

Crossbows can be used with a single hand but take an action to reload.

Bows must be wielded with both hands.

Weapon images are from Dark Souls 3.