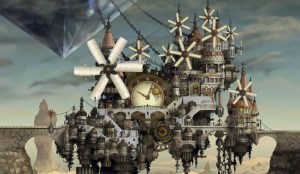

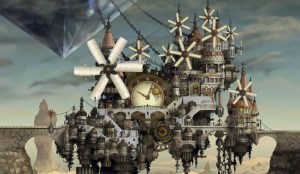

Ancheim, from Bravely Default (source)

Material for tabletop RPGs is often grouped around specific types. For example: spells, monsters, classes, magic items, hexes, dungeons, NPCs, and so forth. Some of these types may be more complex than others. Thus, a published dungeon might include magic items and NPCs. Much of the utility of RPG content revolves around the effectiveness of presentation form. For example, is a monster better communicated as a page spread, with standardized stat section, picture, and extensive fictional ecology, or as a set of incomplete stats and a few sketched sentences? There may be benefits to both approaches. The online DIY scene has generated a number of innovative approaches in this area, such as the one page dungeon template (and resulting explosion of variations on that theme).

Some entities have had more attention than others. Browsing blogs, it is hard not to stumble over new monsters especially, but also classes, spells and magic items. Dungeons require a bit more investment for creation, so there are fewer, but there are still many out there, especially with the one page dungeon contest driving content creation. Towns, however, despite being necessary content for many play styles and an excellent way of communicating setting, are rarely created and shared. By town here I mean any kind of somewhat sheltered and civilized area. PCs may primarily rest, recover, and restock in a town, but a town can also be a site of adventure.

What makes a good town? The canals of Venice, the slums of Midgar in Final Fantasy 7, the clockwork town of Ancheim in Bravely Default, the treetop Inn of the Last Home in Dragonlance’s Solace, the Acropolis of Athens. A town does not have to be strange to be good, though that can be an easy way to add interest, but it has to be distinctive in some way. Places that feel real are memorable. Thinking generally, at least two or three notable features is probably a decent rule of thumb. Extending this to tabletop games in particular, I would also add several specific rules hooks as well, such as Uxa the town of apothecaries being the only place where universal antitoxins can be purchased. Such features give players a reason to care about where PCs are. If all towns are just inns and item shops, location does not matter, but if you can only learn time magic from the Chronomancers of Dundasmael, the town itself becomes adventure fuel in addition to supporting atmosphere and setting.

As an experiment in creating such a location, included below is the town of Gorgonthorn (PDF version), a town perched on crags overlooking deep pools of water where giant crustaceans are harvested and the clerics wear masks. There are many ways that this presentation could still be improved. Gorgonthorn is still too wordy, and more setting could be presented through tables or rules than prose. Further, little attention has been paid to information design or layout directly.

Gorgonthorn

The town of Gorgonthorn is built on rocky scrub-filled highlands. It clings to a collection of perilous rocky outcroppings that are riddled with fissures hundreds of feet deep. Dark pools of frigid water lurk at the bottom of the fissures. Within these waters thrive a hardy form of spiny, cantankerous crustacean known as the vergomult which ranges in size from a single coin to a whole treasure chest. Harvesting the vergomults is dangerous and painstaking work, and often requires descending into the rocky crevasses, and braving the razor-sharp stones. Potential rewards are great for those that are skilled, however.

Wooden walkways and narrow bridges are generally required to navigate between buildings, with the exception of the central market, which is the now-smoothed remnant of some ancient foundation.

Gorgonthorn has no walls, but is defended by three tall, slightly crumbled watchtowers (originally built by some long dead conqueror), high ground, and numerous hazardous deadfalls (some artificial and lined with stakes) which are familiar to the local soldiery. One tower has a functional scorpion siege weapon mounted at the top, generally pointed toward the wilds. Positioned on the edge of ruined badlands, Gorgonthorn is also a common waypoint for adventurers and treasure hunters seeking glory and gold in untracked places.

Laws of note

- Sorcery in town is only permitted by members of the local Order of Mystery.

- Masks must be worn when in public on the weekly holy day (purchasable at the Sacrosanctum).

- The ancient right of trial by riddle is null and void.

Social status is indicated by the extravagance and expense of holy day masks.

Buying items in Gorgonthorn

Most minor items (torches, rations, daggers, rope, etc) can be purchased in quantity (within reason) at rulebook prices. See below for details about merchants and sellers.

More significant items (such as suits of armor, heavy weapons, scrolls of magic spells, potions, and so forth) are limited in supply, only 1 or 2 of each specific kind of item available during any given game session. Items with limited supply should not be assumed to accumulate if PCs do not purchase them, as NPCs are customers as well.

Purveyors of fine adventuring products

Inn

This is Gorgonthorn’s main inn and hostel. Provisions, rations, sustenance, and long-term room lets may be found here, along with Grand Vergomult, the house specialty dish. Basic room and board is 10 GP and will cover one person between adventuring excusions.

- Room and board between excursions (10 GP)

- Prepared ration, one day’s worth for one person (1 GP)

- Grand Vergomult feast, may grant reaction roll bonus (100 GP per plate)

Armory

This unnamed shop is marked by a pair of crossed wooden swords above the door. The proprietor is not a weapon smith, and relies mostly on commerce for supplies, though there are several craftspeople of vergomult chitin that make armor, shields, knives, and arrowheads out of that material.

Order of Mystery guild house

It is said that long ago the Order of Mystery spread across many lands and allowed philosophers to join in profitable congress. Many laypeople still believe that the rulers of civilized lands are little more than puppets of the magisters. Those more knowledgeable know that the Order has long been riven by jealousy and fear into feuding sects, and each guild house is essentially independent. The courtyard garden of the guild house is perpetually in bloom. The current Magister is the ageless and imposing sorceress Arvilia.

Members of the Order may purchase spell scrolls at listed prices:

- Scroll of first level magic-user spell (100 GP)

- Scroll of second level magic-user spell (200 GP)

- Scroll of third level magic-user spell (300 GP)

Anyone may pay to have a weapon temporarily enchanted:

- Enchant a weapon, next attack at +1 and deals magic damage (50 GP)

Sacrosanctum of infinite purity

The Sacrosanctum is a temple of law presided over by three high-ranking (but non-martial) clerics. These priests can craft the items listed below and turn undead as first level clerics, but otherwise have no special abilities. Several jewellers and porcelain sculptors are employed by the Sacrosanctum to craft holy day masks.

- Healing potion, restores 1d6+1 HP (100 GP)

- Scroll of protection, pick between undead or lycanthropes (300 GP)

- Antidote, revive a character slain by poison if administered within one exploration turn (500 GP)

- Bless a weapon, effect as holy water added to next attack (50 GP)

House of the warlock

Technically a rebel and apostate in the eyes of both the Magister and the Sacrosanctum, Tanser Noor has understandings with (or knowledge of dark secrets regarding) the significant town power holders, and thus is tolerated. Tanser’s small wooden house requires navigating a steep, rickety wooden stair (absent handrails) fifty feet down into one of Gorgonthorn’s many crevasses. There is a large bucket on a pulley operated mechanism that Tanser uses to bring supplies between his house and the town proper. He has a sweet tooth and will generally not be home unless a dessert of some type is placed in the bucket and lowered down prior to knocking on his door.

Tanser has the ability to magically conceal his home (the chance of finding a secret door may be used if a full day is spent searching). He generally only does this when outsiders of high office or strange aspect visit Gorgonthorn.

Items available:

- Love potion, as charm person spell, imbiber will fixate on next interlocutor (100 GP)

- Poison, save or die if ingested by human-type (100 GP)

- Voodoo doll, requires a dear possession or part of the target, works on human-types (500 GP)

Other establishments and important locations

Sheriff’s mansion

The town of Gorgonthorn has never had a proper grant of nobility, but it is ruled in practice by the Sheriff, who controls a small, independent soldiery that keeps order and protects the town. The sherif’s mansion is an imposing (but somewhat crude) stone building located across a wide, wooden bridge from the main market square. The Sheriff generally encourages adventurers (as long as they do not stay in town too long), as they bring money and can fulfill frontier bounties without needing to risk proper soldiery.

Ossuarium trevixus

Within this long, low clay brick building are interred the bones of Gorgonthorn’s dead. Proper interment costs 100 GP. The bones of the poor are cast upon the rocks after the flesh is burned away for purification. The ossuarium is operated by the priests from the Sacrosanctum. The building itself predates the establishment of Gorgonthorn.

Vergomulter houses

These cubic domiciles are crafted from clay bricks and shelter the less wealthy residents of Gorgonthorn. The clay bricks are stamped with good luck charms and signs of bounty before being fired. The residences have flat roofes and are often stacked, requiring a ladder for access. Up to two people may reside in a single room.

- Purchase of a residence (500 GP per room)