Three stunt points generated

Green Ronin has developed an RPG based on the Dragon Age video games and set in the same world. Currently, there are two boxed sets out, roughly following the basic/expert example set by Moldvay and Cook/Marsh. Set 1 covers the base system and takes characters from level 1 to 5. Set 2 takes characters from level 5 to 10, introduces character specializations, and includes subsystems for crafting poisons and traps. The system manages to navigate between simplicity and complexity in a very pleasing way, and it is worth looking at for the game even if you are not interested in the franchise that it is based on.

There are eight abilities: communication, constitution, cunning, dexterity, magic, perception, strength, and willpower. Starting abilities range from -2 to 4, with 1 being called out as average. They are determined randomly using a table that maps 3d6 to ability numbers. Characters also have things called ability focuses, which function somewhat like skills but are only very lightly specified. Really, no info other than focus name is needed in most cases, as they are all pretty obvious in function, and are presented in the book without unnecessary padding. More products should take this approach. A simple overview of the system, followed by a list of focuses (organized by governing ability), followed by an example of use in play.

The basic resolution system is 3d6 + ability against a target number, with the potential to bring in an ability focus for a further +2 bonus if it makes sense contextually or is explicitly called for. Thus, one might make a willpower (self-discipline) test, which would be 3d6 + willpower for most characters, but 3d6 + willpower + 2 for those with the self-discipline focus. Attack rolls are handled identically, as each weapon group has a focus; for example, to attack with a sword, a character makes a strength (heavy blades) test. As characters increase their abilities as they level, no separate attack bonus or attack table is necessary to model the increase in competency; the ability test system carries the entire load.

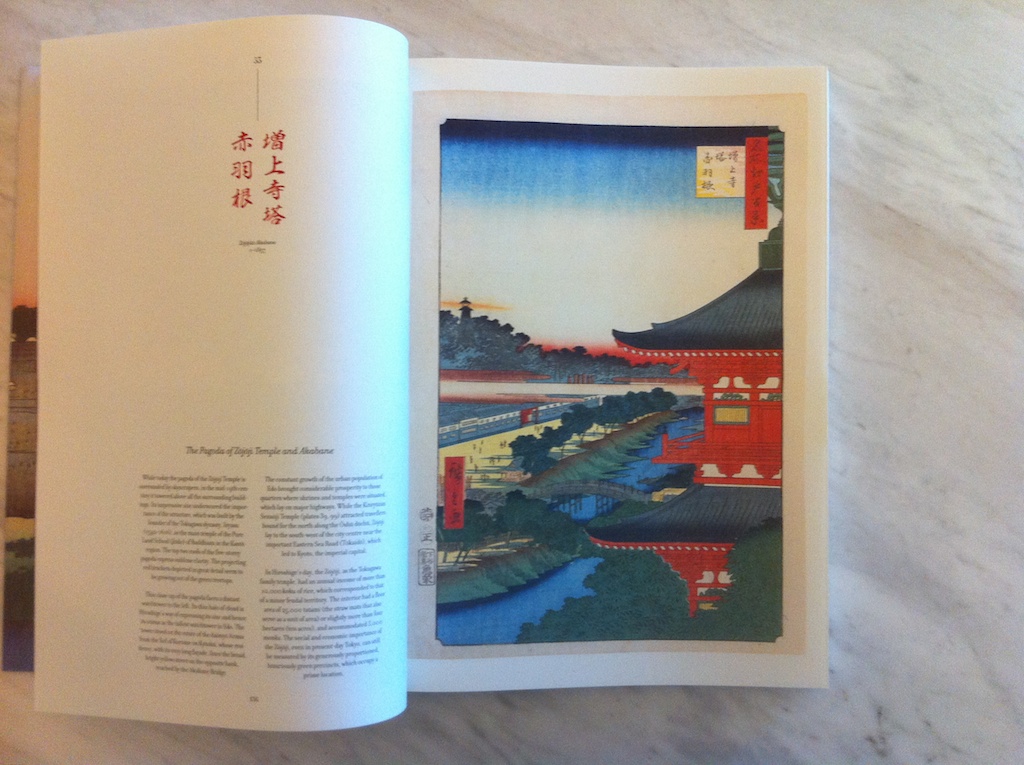

Of the three dice used, one is special (called the “dragon die”) and must be distinguished in some way from the others (three dice come in the Set 1 box with one being a different color). When doubles are rolled on any two of the three dice, stunt points equal to the value of the dragon die are generated. These stunt points can be used for extra effects such as more damage or a chance to immediately cast another spell (for mages).

The character creation process is elegant. I am usually quite averse to character creation with too many options or steps, but the approach Dragon Age takes makes the choices accessible. The procedure alternates between randomness and choice to help players create characters that are not entirely random but nonetheless have some interesting, unpredictable features, guaranteeing that characters of the same class and even background are distinguished mechanically.

You roll for ability scores (having the option to switch one pair), then pick a background, which determines your race and class options. Next, you roll for a random background benefit (which can be something like an ability increase or an extra focus). Importantly, the background ideas are mostly clear without needing to do extended research. So, for example, if you want to play a magic-using character, you take either the apostate or circle mage background, and then follow the procedure outlined in the background (in the case of circle mage, you pick either human or elf, roll for a benefit, and take the mage class). The last few steps involve noting down several basic class features, making one or two more choices from short lists for things like class talents (which further guide the player into choices about things like spells), and then finally equipment (I would prefer a table to roll on for equipment, but even as is it is streamlined compared to “here’s some gold, go buy stuff”). Players end up playing the class they want, in a unique way, without needing to hunt through option lists or feeling like they need to do homework to understand the choices. There is almost zero sense of missing out on synergies due to lack of system mastery despite the large array of possibilities.

If focuses are the AGE equivalent of skills, then talents are the equivalent of feats, in that they further customize and focus a character’s class (thus the difference between a dual-weapon warrior and a two-handed weapon warrior is handled in the system by providing a talent for each). Some direct examples of talents include archery style, poison-making, and entropy magic. The talents available to a particular character are determined by class, so only mages have access to the magic talents, for example, whereas other talents might be available to multiple classes (archery style is available to both rogues and warriors, for example). Each talent has three tiers (novice, journeyman, and master), which become available as the character levels, and each tier offers some benefit. The journeyman level of archery style, for example, allows faster reloading. Mages gain new spells through their talents, which helps balance them against the other classes in a way that does not feel forced.

Many talents do have prerequisites, which I tend to dislike in these sorts of systems, as they often require knowledge of later options before informed decisions can be made about features even during character creation. However, the options are presented in such a logical way, and introduced gradually through the levelling process, that I think this common stumbling block has mostly been avoided (though I would like to see it in play). For some examples, the contacts talent requires a communication of 1 and archery style requires training in the bows group.

It is worth noting that the default assumption of the Dragon Age RPG, in line with the experience of the video game, is a greater focus on combat and tactical play than is usually true for classic dungeon crawling games. Thus, most of the spells are designed for combat (which actually makes sense in the world of Thedas, as mages are only kept around to combat darkspawn, but I digress) and the game does seem to have a slight case of numerical inflation, at least coming from a predominantly OD&D perspective. For example, warriors begin with 30 + constitution + 1d6 HP, and all classes gain 1d6 + constitution HP per level achieved. That’s a lot! To put this in perspective, the bastard sword does 2d6+1 damage and the two-handed sword does 3d6 (with strength also adding to melee damage). Aside: ranged weapons add perception to damage rather than strength, which is a nice touch. That said, my initial impression, looking at monster stats, is not that combat will turn into a slog of HP attrition, but it’s hard to say for sure without playing it. The resolution system using ability tests, is, however, heavily bounded, with opportunities for bonuses few and far between, making me think that the overall power curve of the system is gradual.

Strangely, for an RPG inspired by a video game, scant attention is paid to gear. While this is probably a good thing overall, given how common magical items seems to devalue enchanted items in games that make use of the upgrade treadmill (sword +1, sword +2, etc), it still seems somewhat odd. The example magic items are mostly consumables, and don’t include things like magic staffs that increase spell power. Though Set 2 includes some crafting rules (for poisons and traps), enhancing weapons with runes and enchantment are not covered, despite their prominence in the Dragon Age video game. Perhaps such rules will be included in the upcoming Set 3. While I would rather an emphasis on gear be omitted rather than implemented poorly, even better would be to see the challenge of creating an elegant system surmounted (especially since I am attempting to create such a system for Gravity Sinister). I really appreciate the gradual introduction of complexity behind the overall design, and I can see how introducing enchantment as content for levels 11+ might make sense, though it does feel somewhat off that lower level PCs can’t pay for having enchantments laid on their weapons (for example).

While I am tremendously impressed by the core engine and the character advancement system, there are still some shortcomings. The GM book, other than the monster entries, is mostly a discussion of things like how to deal with player types and plot arcs rather than useful procedures that can be followed. Thus, I don’t think the Dragon Age sets would make a good introduction to the kind of games that I like to run, and though I can see myself running the game pretty much as written in terms of player options and resolution systems, I suspect I would need to import many tools (dungeon stocking, random encounters, reaction rolls, etc) on the referee side. There are some offhand remarks about being open to player choices that seem to caution against preplanned plotting, but little is done to emphasize the “play to find out what happens” ethos (Apocalypse World, page 108) that I think is the true strength of tabletop RPGs.

For another deficiency, the art is extremely bland to the point of being entirely forgettable. There is plenty of world flavor in the mechanics (summoning healing spirits from The Fade and so forth), but you won’t find anything interesting in the visual presentation (I feel mostly the same way about the video game, actually, despite really enjoying many structural aspects of the setting). The mechanical excellence of the system mostly makes up for the aesthetics, in my opinion.

There’s still a lot more to say, such as a more detailed consideration of the mana-based magic system and a discussion of the integration with the default world of Thedas, but I think this post has droned on for long enough. Perhaps I will continue to write about other aspects of the game if I don’t get distracted by something else. Free quickstart rules are available that contain the base system and several pregen characters (though without the full character creation procedure). PDFs of Set 1 and Set 2 can be bought (sans RPGNow-style watermark, thankfully!) from Green Ronin’s web site. Though the physical production of the boxed sets is nothing special (booklets, a few maps, and some quick reference cards), it’s nice to be able to read the books in printed form and I’m not unhappy with the purchase. The Set 1 box includes 3 standard pip-style dice, with one die of a contrasting color for use as the dragon die (I mention this only to make clear that you won’t be getting fancy dice with a dragon icon instead of a 6 or something).

Last word: not perfect for me as a complete game, but probably the best mechanical implementation of distinctive player character development that I’ve read so far.