In Carcosa, almost all of the identifiable tropes of D&D are gone, yet the essence remains. There are no dragons, demi-humans, magic-users, or magic items. There is little overlap in the bestiaries other than the oozes, slimes, molds, and jellies (which are cleverly recolored to fit the setting but otherwise pretty much the same).

In Carcosa, almost all of the identifiable tropes of D&D are gone, yet the essence remains. There are no dragons, demi-humans, magic-users, or magic items. There is little overlap in the bestiaries other than the oozes, slimes, molds, and jellies (which are cleverly recolored to fit the setting but otherwise pretty much the same).

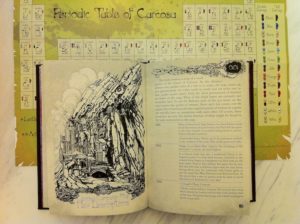

The LotFP version of this book has a somewhat odd status. Originally, Carcosa was published as a supplement to the 1974 D&D rules. Though that was seen as presumptuous by some, it made the intended use of the book obvious, at least to someone who was familiar with OD&D and its supplements. Carcosa the saddle-stapled digest book was easily identifiable as the same sort of book as, for example, Supplement II: Blackmoor. This new release of Carcosa is not, in and of itself, identifiable in the same way, though it is still the same sort of book at its heart. This is not a problem for me, but may be for someone less familiar with the OSR community and OD&D in general.

I have organized my thoughts around the entries in the table of contents, which I arranged into several groups of related items and reordered. These groups represent the five different types of content in the book.

Setting

- Sorcerous Rituals

- Monster Descriptions

- Carcosa Campaign Map

These sections are the most tightly bound to Carcosa the setting. The most impressive thing to me is how integrated all these different parts are. Most games separate these parts (think about the PHB, Monster Manual, and campaign setting split of most D&D products). For example, with every monster is a listing of relevant rituals. And many rituals require components which can only be gathered in specific locations (or must be performed in particular locations). I suppose you could steal a hex here, a ritual there, and a few monsters, but if you just pick and choose bits from these sections, you will not be taking advantage of these linkages. This is a template for how to put together a really engaging hexcrawl campaign. Make all the different categories of rules and setting interrelated. The way the pieces fit together, the whole is definitely greater than the parts.

These sections are the most tightly bound to Carcosa the setting. The most impressive thing to me is how integrated all these different parts are. Most games separate these parts (think about the PHB, Monster Manual, and campaign setting split of most D&D products). For example, with every monster is a listing of relevant rituals. And many rituals require components which can only be gathered in specific locations (or must be performed in particular locations). I suppose you could steal a hex here, a ritual there, and a few monsters, but if you just pick and choose bits from these sections, you will not be taking advantage of these linkages. This is a template for how to put together a really engaging hexcrawl campaign. Make all the different categories of rules and setting interrelated. The way the pieces fit together, the whole is definitely greater than the parts.

I would love to see a reworking of the classic D&D magic system along similar lines. Take all the original spells, flavor them up, and then scatter the components required over the hex map. Up the power a bit so that they are more impressive, and also include elements like making spell X only functional at certain times or in certain places. I would be all over that.

- Space Alien Technology

- Technological Artifacts of the Great Race

- Technological Artifacts of the Primordial Ones

- Desert Lotus

Now we come to the toys. That is, things that PCs might play with. The Space Alien Technology functions, I imagine, much like the magic items function in other games (though obviously with a different flavor). There is a random generators in the back for Space Alien Armament also. The “technological artifacts” are likely to be rarer (like artifacts in D&D). You will notice that three of those four categories are the technology of higher-order beings, which highlights one of the main themes of Carcosa (and, in turn, of H. P. Lovecraft, one of Carcosa’s spiritual progenitors): the universe is a vast and unknown place which was not built for the comfort of humans.

Other than humans (the only option for PCs), there are three other major types of being. Space Aliens are about what you would expect from the name. The Great Race is something like Robert E. Howard’s Serpent Men. And Primordial Ones (also called the Old Ones) are incomprehensible, mostly disgusting, Cthuloid entities (many named creatures taken directly from the pages of H. P. Lovecraft). This forms a hierarchy of beings, with humans on the bottom rung, followed by Space Aliens and the Great Race (I’m unsure which of those should be considered more sophisticated or powerful), with the Old Ones at the top of the food chain. Humans don’t really have anything to their name, other than sorcery (which is really just borrowed from the Great Race).

All of these are well-crafted and evocative, and could easily be dropped into any game, or inspire your own artifacts.

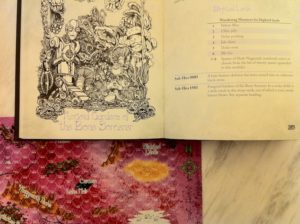

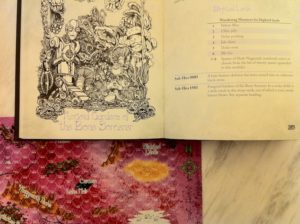

Fungoid Gardens of the Bone Sorcerer

This is an intro module. It also functions as a nice template for how to detail a village without going overboard. Paired with a nice, quick method of randomly generating a village layout (think something like Vornheim), and some practice using such a system on the fly (I’m still getting there), I think this is all you need.

This is an intro module. It also functions as a nice template for how to detail a village without going overboard. Paired with a nice, quick method of randomly generating a village layout (think something like Vornheim), and some practice using such a system on the fly (I’m still getting there), I think this is all you need.

The module is a single 10 mile hex blown up into sub-hexes of 704 yards and includes a number of mini-encounters, adventure hooks, and one small dungeon. I wonder how many such hexes Geoffrey has detailed for his own campaign?

Random generators

- Spawn of Shub-Niggurath

- Space Alien Armament

- Random Robot Generator

- Mutations

This is the most setting-agnostic part of the book, and all of these random generators are easily repurposed, even for games with less gonzo flair. Mutations could be used to add flavor to NPCs, or as the result of a botched spell. The random robot generator is also a random golem (or automaton) generator in clever disguise. The Spawn generator cranks out minor (though still dangerous) Cthuloid entities.

These parts of the book are very strong, and should be useful to every old school ref. One can’t have too many random monster generators (at least, I am far from my saturation point).

New rules

- Characters

- Dice Conventions

At first I felt like the sorcerer class was superfluous. My concern was not originally about balance (the sorcerer might be fighter+, but that comes at the cost of slower advancement). Here is Geoffrey’s explanation for why the Sorcerer is a separate class:

I imagine Sorcerers as men who had to spend 10+ years learning the intricacies of the esoteric language of the lost Snake-Men, and twisting their minds in such a way as to be able to comprehend and effectively perform sorcerous rituals. (Consequently, I can’t imagine any Sorcerers under the age of 30.) Being able to do this is a lifetime commitment. There are no dilettante Sorcerers. Nobody could ever say, “I’m not a Sorcerer, but I’m going to spend the weekend learning how to conjure and bind the Inexpressible Presence of Night.”

And that makes sense to me. It would have been nice if he had said as much in the book. I would probably differentiate the sorcerer a little more, just to emphasize that very difference (a different hit die would work, but for the dice conventions). Also, if sorcerers have spent 10+ years mastering the intricacies of sorcery on such a primitive world, why do they get the same base attack bonus as fighters? I would probably cut that in half, or go the LotFP route and have sorcerers never get better at fighting. The game would also function if you imported any classic set of classes, and allowed anyone to perform rituals given the proper components and configuration, though the feel would change slightly.

I think the dice conventions are important, though they are likely to seem very foreign to many readers. They show the level to which D&D can be hacked and still maintain integrity. I believe a similar idea was originally introduced with either Arduin or Tekumel (I haven’t read either yet, but vaguely recall someone mentioning that on a forum). Personally, I don’t think I would like to re-roll hit dice (and with variable dice type to boot) for every combat, but the idea of re-rolling hit dice per-level or per-session is intriguing. And it means that you might catch Cthulu on an off day (though one might argue the same thing could be achieved with less overhead by just rolling hit dice, as you could still roll all ones). I think there may be a typo in the dice conventions table lookup example. A minor issue, but still unfortunate given that I can see this section being confusing to some.

Conclusion

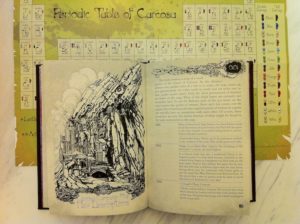

This is a fantastic book, and a fantastic toolbox for classic D&D. It is perhaps the most aesthetically attractive book in my RPG collection. Oh, and did I mention the art? It is wonderful. All by Rich Longmore. I like the unity. This is art direction done well. Like the Planescape of Tony DiTerlizzi (which is a setting that I have come to not particularly care for, though I still adore it for the art). I didn’t expect this, but I find myself wanting to run Carcosa out of the book, no house rules, completely on its own merits (I had planned on just using it as a toolbox).