Unlike D&D, Torchbearer uses a dice pool system for task resolution. When making a test, a number of six sided dice is rolled equal to the stat or skill in question, with bonuses causing extra dice to be added to the pool. Three or less on a die is a failure and four or more is a success. Every roll is versus an obstacle number (essentially, a difficulty class) which is set based on the number of factors involved in the particular test. Factors may be set by referee ruling but are also explicitly listed in the rules along with most stats, and the lists of factors seem to be rather comprehensive.

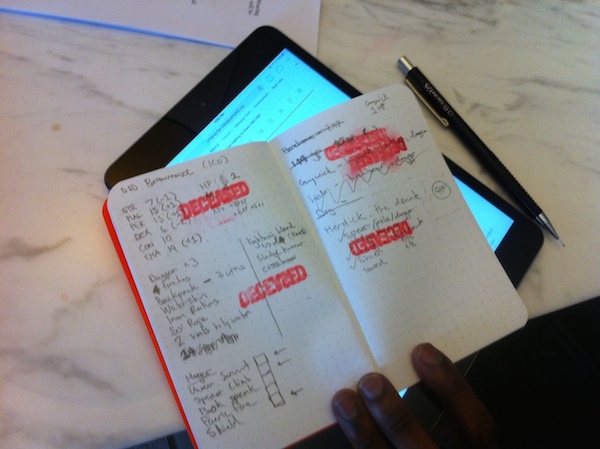

A PC’s character sheet is made of an array of stats which include many terms similar to those found on a D&D character sheet, such as stock (which means race), class, will (which stands in for the mental ability scores), health (which stands in for the physical ability scores), and skills. However, there are also a large number of other game constructs which may seem more opaque to a D&D player, such as traits, wises, a belief, a goal, an instinct, and several others. It is important to emphasize that these are not merely descriptive. For example, acting on a belief during a session earns a PC a special kind of resource at the end of a session (called a fate point) which can be used in several ways. Triggering an instinct allows a roll that does not cost a turn. And so forth. I admit that the diversity of systems that a player has access to for augmenting rolls in specific contexts is a bit bewildering, but I suspect it becomes more tractable with experience. That said, these are systems that players will need to learn how to use to be maximally effective.

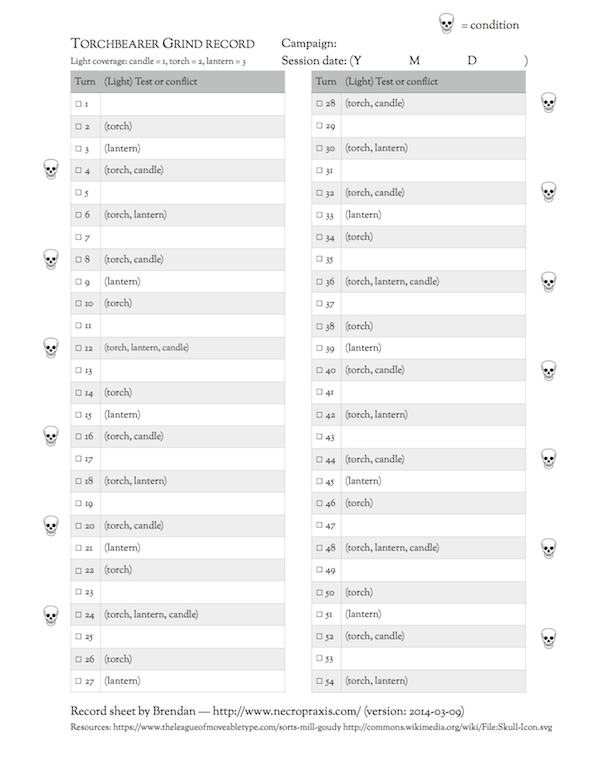

Torchbearer uses a turn structure heavily. As written, D&D does, too, though in the case of D&D, turns are often hand-waved in practice, with dialectical narrative quickly taking over. Within an adventure, every test or conflict costs one turn. PCs earn a condition for every four turns that pass. Conditions are similar to a health track, and include hungry, exhausted, angry, sick, injured, afraid, and dead. Most of these conditions can be recovered from explicitly with skills, equipment, or spells. Rations, for example, can be used to eliminate the hungry condition. Light sources deplete as turns progress (torches in two turns, lamp oil in three turns, and candles in four turns). Light sources also only explicitly cover a set number of PCs, and any PC not covered by a light source has test obstacles increased. (I will almost certainly find a way to use a similar light coverage rule with D&D at some point.)

In addition to turns during the adventure phase, there are several other phases, including camp and town. Camp and town phases are used for different kinds of recovery. After three adventures, there is a winter, which affects the next phase (either town or adventure). Resources are more dear during the winter, but there are also several special opportunities available to PCs for learning and improving skills. Adventuring in the winter is more dangerous (conditions are earned every three turns and exhausted, injured, or sick can all lead directly to death). The important takeaway here is that time moves forward in a structured manner directly tied to game mechanics.

Value is handled more abstractly than you are likely used to from D&D. Instead of recovering treasure, calculating its exact GP value, selling it, and them buying things with the proceeds, everything is modeled as bonuses to a roll. To buy things in Torchbearer, you need to test Resources, and prices are handled as obstacles to a Resources test. Treasure is listed as a die value, and serves as a temporary bonus to a Resources test. After being used, recovered treasure is removed from a PC’s inventory. This makes it seemingly much harder to accumulate significant wealth.

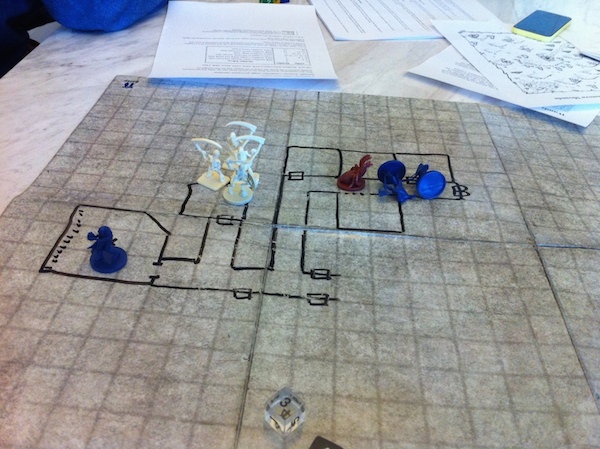

Conflicts (which include, but are not limited to, combat) are team, rather than individual, based. One player takes the role of conflict captain, who serves as the coordinator (from a rules perspective) of the team. Every PC participating can help, but each team specifies only three actions (from attack, defend, faint, and maneuver) per conflict turn. The actions are assigned to different PCs if possible and revealed in sequence in opposition to the opposing team’s actions, leading to a kind of rock, paper, scissors dynamic. Specific skill tests to accomplish the different actions vary based on the kind of conflict in play. There are eight different kinds of conflict specified, and custom conflict types may be improvised as well. Just for one example, the Convince conflict uses the Persuader skill (for Attack and Defend actions) and the Manipulator skill (for Feint and Maneuver actions).

Each team has a disposition which is determined for the team as whole based on skill rolls, and then divided into individual pools of HP by the team’s conflict captain. Unlike HP in D&D, disposition in Torchbearer is separate from health conditions, determined by skill rolls, and per-conflict. This emphasizes its abstract nature and also changes the resource dynamic of HP. Conditions persist (and may serve as factors for test obstacles), but disposition (and thus HP) is determined separately for each conflict.

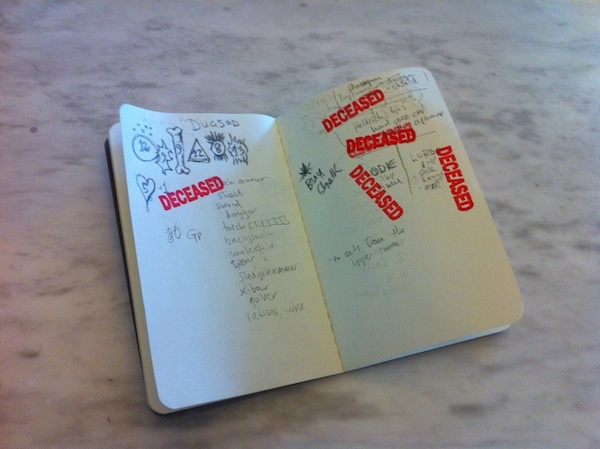

Advancement occurs in a much more fine-grained manner than in D&D, which hooks most character development into the process of gaining levels. Abilities and skills improve automatically after passing and failing a certain number of tests, based on the current rating (the P and F bubbles on the character sheet by skills are used for this purpose). Increasing character level occurs after spending a set number of fate and persona points. New levels grant abilities similar to what you might expect, such as more spells for magicians and various extra abilities for other classes, generally phrased a choice between two options. What this means is that the driver of character development is making tests and spending the metagame resources of fate points and persona points, not treasure recovery directly (in contrast to D&D).

It is worth emphasizing that I am not an expert in Torchbearer at all. This post is just as much a method for me to get a handle on the mechanics as it is to communicate them to others. (In fact, that sentiment could be expanded to cover the entire project of this blog.) There is a lot that I have not covered, but hopefully this will be a useful starting point nonetheless.

Players will likely be interested in the Torchbearer free PDF bundle, which includes a handout summarizing the conflict rules.