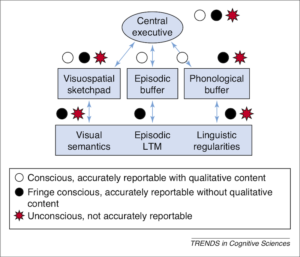

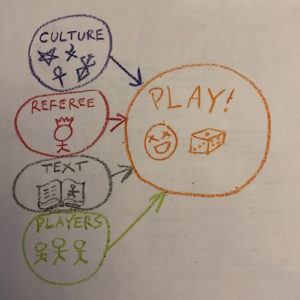

Oversimplified schematic

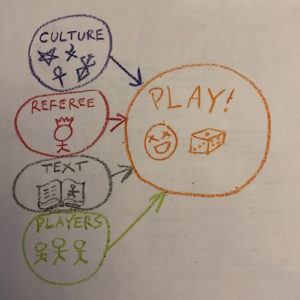

A longstanding fault line in thinking about the design of tabletop roleplaying games is belief about the influence of system on resulting play experience. The System Does Matter manifesto, and other discussion centered on the Forge forum, argued that game designers could shape play experience systematically by focusing their design on theoretical concerns, communicated to players through language in game texts. Though this approach has undoubtedly influenced mainstream and niche games, the most successful games remain stubbornly unfocused and the experience of play using a given system seems highly variable. Considering the approaches different schools of psychology take can help provide an explanation. Both game design and game facilitation are, after all, forms of applied psychology. Particularly, it seems to me that the various influences on resulting play can be understood as play culture, referee, text, and player engagement.

For my purposes, a rule is a procedure that guides play. Guidance can either call for player behavior, such as to roll a twenty-sided die at a particular time, or clarify some aspect of the shared fiction players collectively imagine, such as whether a monster falls into a pit. A system is the collection of rules that players endorse and use, either by heuristic (“it is in the book”) or explicit. It is impossible for any system to completely determine the experience of play in the same way that it is impossible for a legal code to completely determine the behavior of people in a state. Similarly, the system must have some effect on the experience of play if players ever look to the rules for guidance regarding appropriate behavior or to determine the state of shared imagination.

The influences described above break down into causes involving culture, individual people, and situations. The effects of referees and player engagement are both influences of individuals. The referee, for games that have such a role, tends to be comparatively more influential between these two factors, even though the number of players is usually greater, as the referee has more wide-ranging responsibilities for facilitating the play experience.

Personality psychology studies the influence of stable individual differences on psychological outcomes. For example, a referee that can do entertaining voices will likely bring this ability to any game they facilitate, from D&D to Dark Heresy. Referee preference for extensive preparation is another example of referee individual difference affecting play experience. Presumably, many more general personality differences, such as extraversion and optimism, will also affect the play experience systematically.

Social psychology studies the influence of situations on psychological outcomes. Incentives, norms, and goal cues are examples of ways situations can influence psychological outcomes. In the roleplaying context, the structure of experience point rewards is a situation effect. Game texts, and other table paraphernalia such as maps, are features of the situation in these terms. Every time players look to the text, the situation affects the play experience. It is worth noting that texts are made up of more than language, also including art, layout choices, and so forth.

Play culture differs from situation in, among other ways, that culture is more diffuse, less immediate, and more persistent. A group can run a B/X D&D game for some time and then start a new Call of Cthulhu game. This changes an aspect of the system, but may affect play culture minimally. It is possible for people to move between cultures, such as when a person moves from a family context with particular ethnic assumptions into an institutional culture, such as school or a company office, but it is generally harder to move between cultures than it is to affect situations. Unlike situations, cultural influence generally requires socialization, distinct symbol systems, and deeper, often unexamined, assumptions1.

The ranking of influences presented above helps explain the diversity of play experiences. For example, in one play culture, Burning Wheel is a comedy engine. In another, it is a genre emulator. In one play culture, Pathfinder is a carefully tuned tactical teamwork engine. In another, it is a competitive exercise in character optimization. The Pathfinder Core rules explain some shared variability in the play experience, such as how numerical character ratings affect aspects of the shared imagination. This kind of character has a greater chance of hitting in combat than that kind of character. This monster will behave in a particular way if player characters take certain actions. However, the play culture shapes when and how elements of system take the stage. To accept this neither dethrones the influence of system nor casts players as pawns of innumerable, clever system nudges.

This way of thinking about games leads to several conclusions. First, the play culture likely shapes play experience disproportionately because the influence is less immediately visible. This is why dropping into a group using ostensibly the same rules can feel so disorienting. Consider the slightly stylized example of a fifth edition D&D game using Curse of Strahd in the mainstream game store play culture compared to a fifth edition D&D hex crawl in an OSR culture expecting emergent narrative and diegetic problem solving. Similarly, groups participating in the mainstream Pathfinder play culture are likely more similar than different, in terms of play experience. Participating in a Dragonsfoot-style Grognard culture, whether running AD&D or some other set of rules, probably leads to a more similar play experience than looking at the AD&D text independently, as a primary source of system, or the particular referee. This suggests that roleplaying game designers should pay more attention to exploring and understanding play cultures if the goal is to affect the experience of play.

For statistics nerds

Y = Xculture + Xreferee + Zsystem + Xtext + Xplayers + ε1

Zsystem = Xculture + Xreferee + Xtext + Xplayers + ε2

Where Y is play experience.

In the figure below, I have highlighted the effects that I think are particularly important:

There should really be subscripts on those error terms, but you get the idea

There are probably some edge cases, which would show up as error in the above model.

Alternative models

Referee primacy

Y = Xreferee + Xplayers + ε

This is play experience being primarily determined by group (coordinated by referee), as argued in Robin’s Laws of Good Game Mastering (2002):

What really makes a difference in the success or failure of a roleplaying session is you [the referee] … Our biggest task as GMs is to direct and shape individual preferences into an experience that is more than the sum of its parts.

GNS

Y = (Xsystem × Xplayers) + ε

GNS (gamism/narrativism/simulationism) hypothesizes a fit effect interaction between system type and player priority. The System Does Matter article is from 2004.

PIG-PIP

Y = Xparticipants + ε

The 2018 PIG-PIP formulation (Participants Invent Games-Participants Includes Paraphernalia) gives system a metaphorical seat at the table:

7. The Basic PIG-PIP Claim: Participants determine the character and quality of a game experience. In addition to the players and GM, “participants” includes paraphernalia used during the game and preparation for the game–game texts, house rules, miniatures, tables, chairs, the physical or virtual space the game is played in, snacks, etc.

1. I am mostly ignoring cognitive psychology. Though it is one of the major schools of psychology, it seems less relevant to the play experience of tabletop roleplaying games. This could be a bias on my part. However, the minimal influence of cognitive psychology on tabletop play experience seems like a key way in which tabletop roleplaying games differ from the more passive, less creative experiences evoked by video games and audience media such as movies and novels. ↩